Why the Vaccinated Account for 50% of COVID Infections In Israel

The headline seems alarming, but the mathematics of vaccine efficacy says that this is to be expected

As more and more people have gotten a COVID vaccination, there have been more and more news stories about vaccinated people catching COVID. This can seem worrying and alarming, but there is a phenomena known as the “base-rate fallacy” that cleanly explains this. I found it fairly hard to explain with text but it was incredibly easy to see when I created an interactive visualization and played around with the numbers myself.

So I created this video, which I hope helps. The text of the video is replicated below.

As we shift into the late stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, I recently realized that we’re going to have an entirely new string of news stories and headlines that will, at first, seem very alarming. I came across this very illuminating thread from Jeffrey Ely.

He was reading a piece about a recent COVID surge in Israel and notes how “half of all newly infected adults in Israel had been fully vaccinated” and how that phrase makes it sound like vaccines aren’t offering the protection that we had hoped. This fact, taken all on its own, seems to coach us towards despair. But the Jeffrey walks through the details of something called the “base rate fallacy”. I loved how he walked through the mathematics of it, and it inspired me to recreate this concept in a visual form.

What we have here is a representation of the FDA trial data that was used to approve the Pfizer vaccine. They recruited about 37 thousand people, gave half the vaccine and half the placebo and tracked them over 4 months. Over that 4 month period, 172 of the unvaccinated people caught COVID and only 9 of the vaccinated people caught it. This gives us what I’m calling a “natural infection rate” of 1 percent. That means that 1 percent of unvaccinated people caught COVID over those 4 months. Because only .05% of vaccinated people caught it, that is how they calculated the vaccine efficacy rate at 95%.

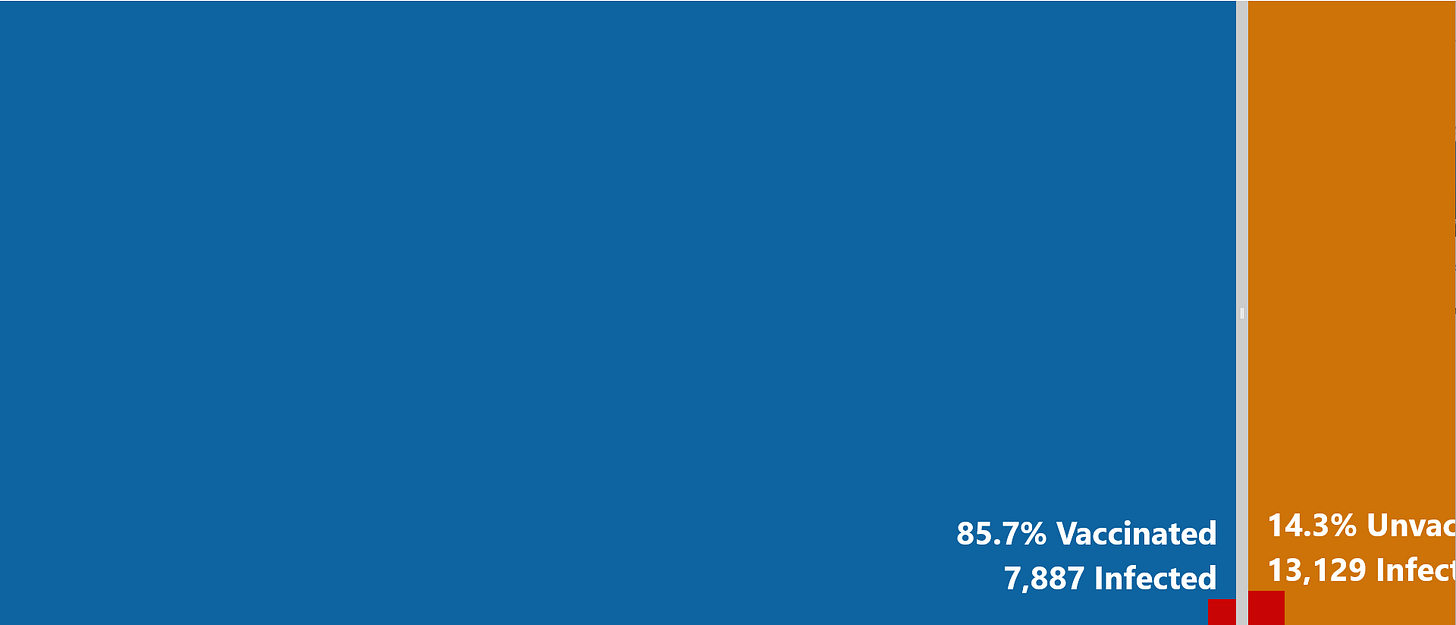

As we’ve deployed the Pfizer vaccine into the wild, it turns out the efficacy is more like 90%, so lets just change that variable here. Now let’s increase our sample population to the Israeli population, about 9.2 million. Israel has been one of the leading countries in the world on COVID vaccinations with about 80-85% of adult already vaccinated. We can see that, as I move the slider here, the infected unvaccinated number shrinks. This isn’t because the unvaccinated are more protected but because there just aren’t that many of them left. The pool of unvaccinated individuals is small, so the number infected shrinks.

In the same way, there are now so many vaccinated people that, even though they have 90% protection against the virus, they end up representing a pretty sizable portion of the cases. There is even a counter intuitive phenomena in which, if vaccination rates get very high, we could end up with the majority of COVID cases among the vaccinated.

This isn’t very intuitive, so I added another component to this visualization. I wanted to show how many people are protected by the vaccine.

What this box represents is the number of people who *would* have caught COVID if they had not been vaccinated. These are the people who ended up fully protected as a result of getting the vaccine.

There are a lot of other things this visualization lets us see. I used a “natural infection rate” of 1% because that’s the rate we saw in the Pfizer study. But, over time, the infection rate will be higher than that. Officially, about 10% of Americans recorded a positive COVID test and it’s very likely the number is closer to 20%.

If we assume that another 5% might still catch it, we can plug that number into this visualization and see that vaccines will protect millions from catching and spreading COVID in the future.

There are some other interesting things we can see with this app. If we change the sample population size to 100 thousand, we can play around with some of these variables while getting manageable and even numbers. Let’s set the “natural infection rate” to 3% and set the vaccinated rate to 50%. With a 90% effective vaccine at 50% vaccinated, we get a total of 1,650 infections (150 vaccinated + 1500 unvaccinated).

But if we set the vaccine efficacy to something like 65% (which is the efficacy of the AstraZeneca vaccine), we can have 68% of the population vaccinated and end up with that same overall rate of infection (727 vaccinated infections + 923 unvaccinated infections = 1650 overall infection rate).

Now, I think you should still get the vaccine, even if it’s a lower efficacy number. Something is better than nothing and every little bit helps. But what we can see here is that judging COVID numbers in the future is going to be extremely complicated. Yes, more vaccinations are good, but the difference between 60% vaccinated and 75% vaccinated is not a huge difference.

There seems to be a sense among some people that we just need to hit some tipping point with vaccine administration and the pandemic flips from “on” to “off” but that’s just not the case. It seems very possible that, even with a highly vaccinated population, we will still see COVID surges to one degree or another.

Of course, this is an extremely simplistic visualization with very few variables. It doesn’t account for natural immunity, or the role that vaccines play in reducing COVID spread or reducing the severity of the disease. We certainly expect (at I expect) that vaccine are going to make everything better on pretty much every metric. But they’re not going to “stop” COVID in the sense of making it disappear. At some point or another, we’re going to have to accept that COVID is an ongoing disease, protect ourselves the best we can, and go on with our lives.

Looney Tunes: Fast and Furry-ous

Whenever I tell my kids to go watch some Looney Tunes, my 5-year-old son always wants the roadrunner shorts. These are the kinds of shorts that would have made Walt Disney seethe with anger at the lack of narrative, the endless simplistic predictable gag-a-thon of it all. But I’m convinced that there is something about creativity within a format that really appeals to kids. They don’t have to spend time trying to figure out what is going on, they know what is going on. They can just laugh at each individual failed attempt at catching the roadrunner.

This is the first of the Road Runner / Wile E Coyote cartoons. It’s a little funny to me that, while most of the other Looney Tunes characters went through an evolution to become the character we are familiar with, the Road Runner / Coyote dynamic pretty much nails it on the first time around. The gag-flow works really well, with the attempts to get the road runner accelerating into an over-creative over-complicated absurdity by the end of the short. I like to think this is a parable of technological progress and how over-thinking problems doesn’t actually lead to better solutions, it just leads to more complicated failures.

This was so helpful, I became a paid subscriber just to let you know. Thank you

Good video.