Why I Am Obsessed With the Forbidden Seuss

I love art, I love people, I hate censorship, and history exists even when we don't want it to

This has nothing to do with COVID and for that I apologize. If I had to make the case as a pundit who needs to connect what he says to everything else he has said, I would say that censorship is like a virus… it spreads and infects and kills, crap crap crap, this is going poorly, let’s ignore that metaphor and just move ahead.

How a Cultural Liberal Became a Cultural Conservative Without Moving an Inch

An Argument From History

For The Discovery and the Wonder

Turning Love Into Shame

We Don’t Know Who We Are If We Cancel History

How a Cultural Liberal Became a Cultural Conservative Without Moving An Inch

Two weeks ago, Dr Seuss Enterprises announced that they would no longer print six Suess books due to what they described as “insensitive and racist imagery.”

I’ve been rather… um… energetic about this topic on Twitter. Part of this is in response to what I see as rather dishonest attempts to justify this decision within the context of a culture that grew up righteously singing the praises of banned books and encouraging people (especially children) to pursue “forbidden knowledge”.

I went to college at a time when the people most likely to “ban” a piece of art were the conservative Christians. Whether it was a book, a movie, or some artifact of fine art, the cultural group most eager to remove access to art was on the right. Terms such as “pornographic” and “inappropriate for children” are commonplace in requests to remove books from library shelves.

In fact, for the purposes of a “banned book list” like the kind that is published by the American Library Association, the very definition of a “ban” has nothing to do with if a book was actually removed from a library but is a catalogue of how often people have requested that a book be removed from a library. With that definition, it has been argued that this removal of Seuss books from publication isn’t even truly a “ban” because it comes from Dr Seuss Enterprises and not from community complaints. Even as libraries remove the books from their shelves, it’s not formally considered a “ban” by the ALA because, instead of a library patron impotently complaining about a book, the library is using its institutional power to remove it.

It bothers me somewhat that books that you can easily purchase or check out of any library are considered “banned” while books that you actually cannot obtain are “not banned”. If this is the case, then perhaps we need to revisit our definitions.

Regardless of the actual definition of the word “ban”, I want to make a distinct plea for continuing publication of these books, even if we must ultimately do so without the permission of the publisher.

An Argument from History

I want to start this conversation by asking you to watch this video that appears at the beginning of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection Volume 3

I remember when these DVDs came out and there were some complaints among collectors that they shouldn’t have to watch this video to see the Looney Tunes shorts or that this warning was infantilizing and insulting to the viewer. My position at the time was that I was annoyed by it, but I’ve grown increasingly sympathetic to it. Furthermore, if the price of having the Warner Brothers studio restore and release these 80+ year old cartoons exactly as they originally met their audience is that Whoopie Goldberg talks to me about racial and ethnic stereotypes, I consider that a fair trade.

Goldberg has long been a staunch advocate for preserving the film history in its original form. Hell, she’s argued that Disney needs to re-release Song of the South for a new generation. She’s argued that the crows from Dumbo are an essential part of our collective cultural memory. She really believes (as do I) that we shouldn’t let even obviously offensive media fade silently into the past but we should keep visible and accessible for future generations.

This is a good argument for maintaining the publication of these Seuss books. But it is not the one that really moves my soul.

For the Discovery and the Wonder

Before this story broke, I had read only And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street and On Beyond Zebra.

On Beyond Zebra was certainly my favorite. It tells the story of an older boy who, watching his young friend spell out the alphabet, informs him that there are another 19 letters in his alphabet. Without these letters, we learn, you couldn’t possibly talk about all the glorious things out in the universe.

There is one letter, ZATZ, is essential for spelling Zatz-it. Without this letter you couldn’t possibly comprehend the Zatz-it, a gentle giant of a creature that requires a special nose-patting extension to fully appreciate.

What I love about On Beyond Zebra is the sense of the incompleteness in our existing knowledge.

Back in the world of adults, we often forget that our knowledge is quite limited. We don’t know everything, and we can’t know everything. But, beyond that, we don’t have the mental constructs to know everything. Our children will discover new mental constructs that will enable them to navigate the physical world in a way we currently cannot. They will come up with new vocabulary to describe things we literally cannot imagine… because we don’t currently have the words for it.

On Beyond Zebra is about that. It’s about the idea that we can expand the very building blocks of knowledge, down to the letters that we use to construct the words necessary to describe the world around us.

That’s a valuable thing to understand. That’s a deep knowledge to toss in front of children and yet Seuss does it beautifully.

And now it’s gone.

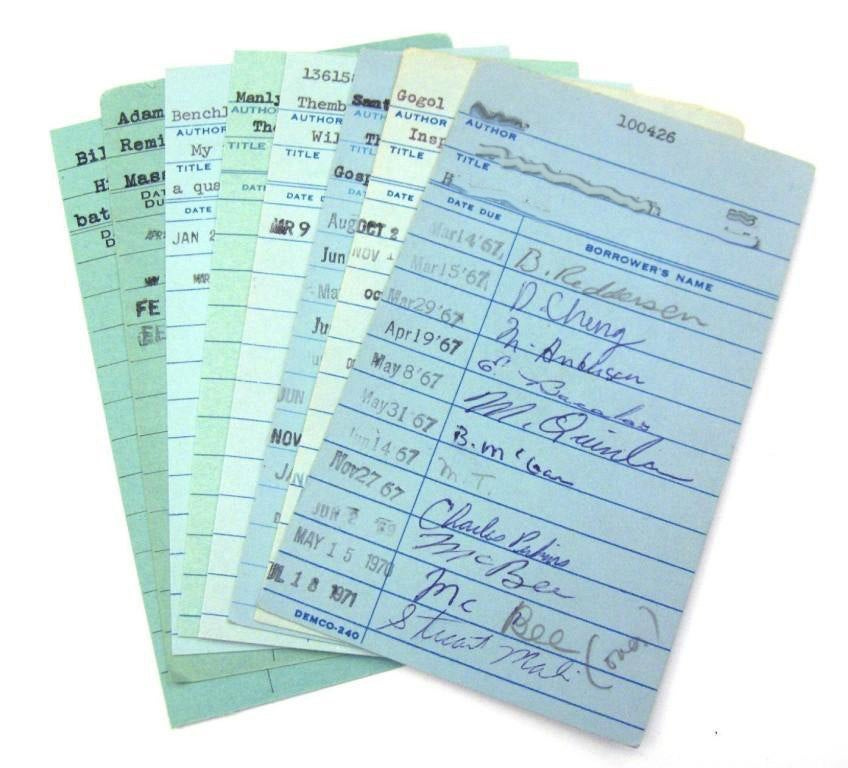

Each of these books has a dear advocate. Each of these books had a kid who loved it more than any other book in the library. If you’re old (like I am) you remember checking books out from a library, signing your name to the checkout card every time you needed to read that book again.

For those under 35, this is a checkout card. You would sign your name to it and the librarian would stamp the date-due box to remind you when to bring it back.

Confession: There is a copy of The Dark Knight Returns in the Fairport Public Library where, if they still hold those library checkout cards, you may find my name scrawled repeatedly in the checkout card. It was my favorite book for many years. I’m glad a public library gave me access to a book my parents wouldn’t have let me buy.

Back to the point… each of these Seuss books had a checkout card where you could see the same kid (or parent) checking it out again and again. Each of these books was beloved by someone. And that love has been taken from them.

Children will never again see themselves in the boy of Mulberry Street, whose imagination on his walk home from school took a a horse and wagon and turned it into a grand town-engulfing procession. They won’t look into the depths of McElligot’s pool and wonder about how this little pond in their town leads out to the ocean and, therefore, into every corner of the world.

These stories aren’t disposable. They are not replaceable. They inspired people and brought them joy. They are something to be protected and cherished. They should endure.

But their lives are over. These stories did not die from neglect. They were killed by a publisher who feared that a few outdated moments in these books would be used as a weapon against the larger Seuss enterprise. They were sacrificed in order to hold back a tide of unsympathetic, vengeful, artificially generated offense proffered by activists itching to show their power over the larger culture by strangling the childhood memories that these people cherished.

Turning Love Into Shame

The execution of these stories isn’t even the most anti-human part of this story. That part is reserved for the people who decided the appropriate tactic in this culture war skirmish was to attack as racists anyone who loved these books.

Sadly, this argument even came from people I respect, like Jake Tapper.

Think of a piece of art that you love. Pick any one, it doesn’t have to be a Seuss book. It could be Harry Potter or Hunger Games, maybe it is a mainstay of Russian literature, it could be a play like Rent or a movie like Pulp Fiction. Think about how much you enjoy it, how your eyes soften and the corners of your mouth turn upward into an involuntary smile when you think about it.

Now imagine someone tells you that you’re a racist for loving that thing you love.

What is the appropriate recourse?

Do you object to being labeled a racists for loving something that brings you joy?

“Well,” they would say (and indeed they did) “only a racist would love that thing. Are you going to disagree? You must be a racist too!”

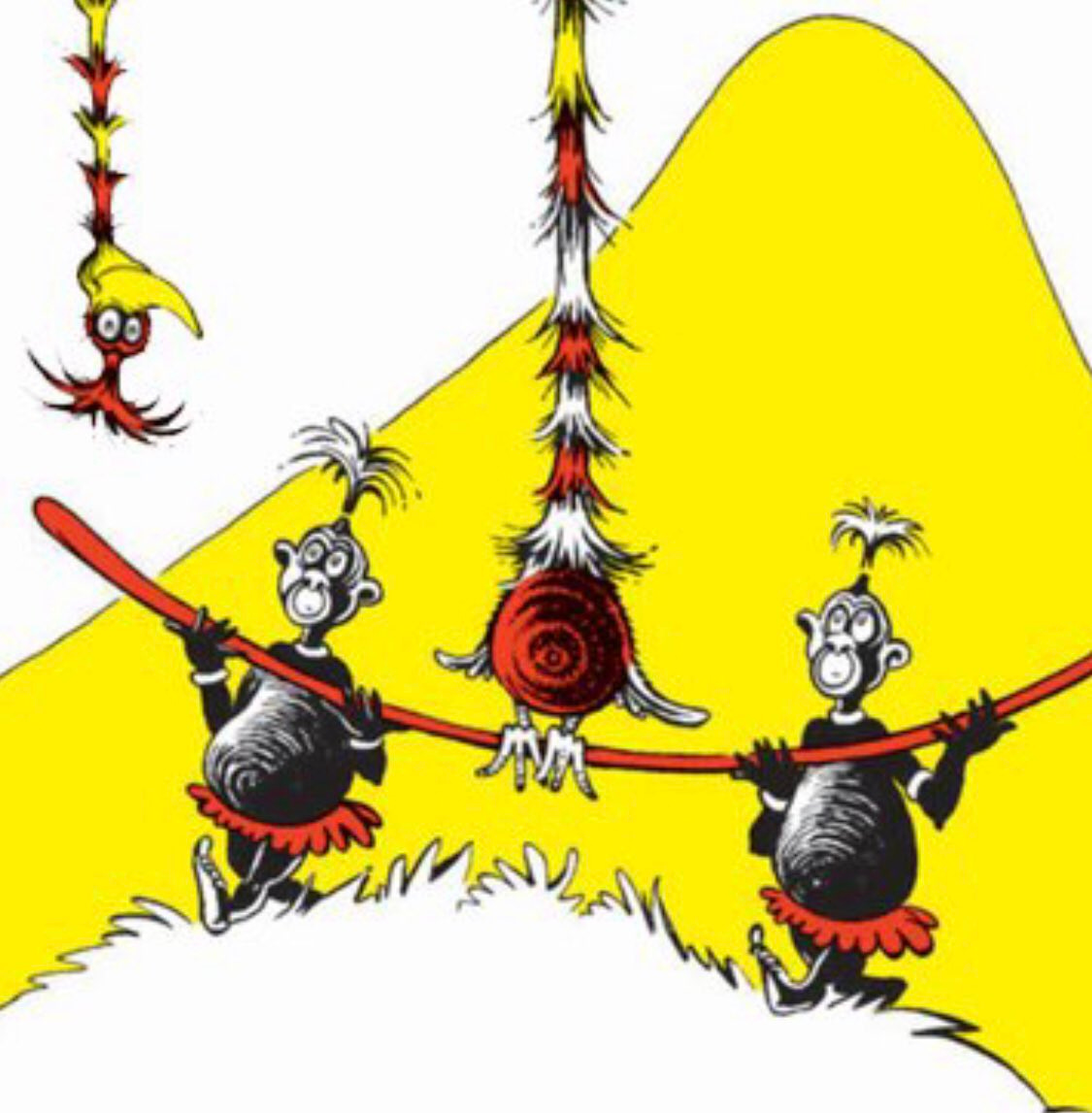

Here is the racism that Tapper objects to from On Beyond Zebra. I show this to you because Jake Tapper did not. Keep that in mind. Tapper picked the most offensive image he could find (from If I Ran the Zoo) and pretended like that was the only example anyone needed to see.

But he told his audience this image from On Beyond Zebra was “indefensible” even though he didn’t show it to them.

Now, because I’m not stupid, I know the objection to this image. It is that this is a Middle Eastern stereotype based on the the fact that he’s riding what appears to be a camel. But I’m at a loss about what the negativity is here. Is it that Arabic people hoard things? Not only do I not get that from this image, that’s not a thing I’ve ever heard. The objection seems to be that it’s bad to cartoon-ize any ethnic group whatsoever.

Here is the offensive image from McElligot’s Pool.

I suppose the idea is that the concept of Eskimo Fish is offensive. That’s all I’ve got on this one.

There is a group of people who are trying to shame those who loved these books, calling them racists, implying that their defense of historical art means that they hate minorities. This is not a thing anyone believes. No one actually thinks that the people who continue to love these stories are racists. They’re using it as a form of control. They want to put anyone who dares love the book they’ve cancelled into a defensive crouch, to force them to defend themselves against the accusation of racism and hatred.

This attitude comes in a variety of flavors. There are the ones who will just out-and-out say that the people who love these books are racist, but there are others who think they are taking a softer, more compassionate tact by saying “There are thousands of wonderful children’s books to choose from, why do you have to be attached to these specific ones? Why can’t you just abandon those books and shift over to these new not-banned books?”

While very different in tone, these attitudes are (in my view) almost identical. It’s an attitude that says “nothing is unique, nothing is special, everything is replaceable”. I’ve seen this attitude applied to art and I’ve seen it applied to people. It’s repulsive to me.

Yes, there are thousands of short cartoons, but there is only one China Plate (which I reviewed here). There are thousands of movies but there is only one Pulp Fiction. It’s OK to love and admire these things. It’s a deeply ugly side of us that tries to tell people that their love of a particular work of art and their objection when it is taken away from them makes them a bad person.

There are people who take pleasure in shaming someone today for loving a book or movie that no one else cared about yesterday. This is an inclination that prefers destruction over creation, criticism over encouragement, and shame over joy. This is form of Puritanism that is anti-human and takes pride in wielding power to cause grief.

I reject it entirely.

We Don’t Know Who We Are If We Cancel History

What I’m not trying to argue is “these images can’t possibly be offensive”. It’s obvious that the image that is most often held up as an example (seen below) is, in fact, an offensive image to many people. The characterization of African people, while fairly typical in the early part of the 20th century, is now quite offensive.

I’m not interested in becoming the offense police, rating all images on an offense scale and saying that everything that scores over a 7.8 is ok to ban while everything that is 7.7 or below is permissible for now (but probably won’t be later on).

Even if the images *are* offensive, that’s not a good reason to ban them. Let’s make no mistake, when a publisher refuses to publish a book, when the books are ripped off the library shelves, when multiple Big Tech companies tell independent book sellers they are no longer allowed to sell a book, that book has been banned.

I hate a culture that bans things. If we banned all bad things, we would have so little aged culture that our entire history would be obscured. Our culture is filled with bad images, especially ones that are many decades old.

The first major motion picture was Birth of a Nation, a groundbreaking piece of cinema that singlehandedly introduced us to the concept of long-form moviemaking. It was also a vile, racist, pro-KKK work that nevertheless taught future filmmakers the essential components of the grammar of this new visual medium.

The first sound picture was about a Jewish actor in blackface who sings “My Mammy” for his public audience and “Kol Nidre” for a Jewish one. At the time, the Jewish portion of the movie was edgier than the blackface component.

You can’t see the performance that won the first Oscar for a black man because Disney hasn’t released Song of the South for a generation. If Gone With The Wind is ever cancelled, you won’t be able to see the performance that won the first Oscar for a black woman.

These movies, this art, tells us where we came from. James Baskett wasn’t an unwilling participant in Song of the South. He gave a stellar performance and was on excellent terms with Walt Disney (who was deeply involved with and very proud of that production). We need to see these things and ask ourselves why such talented performers took these roles that we would now consider beneath them.

We need to understand that it is because they lived in a time with different assumptions. They lived in another context. The only way to understand that time is with more information. We need to read their stories and see their films. We need more books, more cartoons, more art, more of everything. Every piece of art, every book, every film, they all contribute to a fuller understanding of where we came from. Offensive or not, they tell us something about ourselves.

I don’t imagine this plea for understanding and the integrity of art will change many minds. In fact, I’m actively planning that it won’t. I’m planning to privately secure all the “forbidden” knowledge that I can and make it available to my family and friends. My dream is to print out the Forbidden Seuss and bring copies to my local book store when they hold their “Banned Books” events. They will be making bank, selling books that are clearly not banned, while I spend my own money handing out copies of books that you literally cannot buy.

I feel like an absurdist in saying this. Am I truly planning to spend my waning years handing out home-printed copies of beloved works of art that Big Media says you aren’t allowed to have?

Honestly, nothing could make me happier or make me feel younger.

Looney Tunes: Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid

This is quite an early Bugs Bunny cartoon, but we still see a lot of his personality shining through. In this short, Bugs is up against a dumb vulture who is out to get Bugs because his mother downgraded his target animal from a horse to a rabbit.

Naturally, Bugs makes a fool of the vulture, but also makes a fool of himself through a strategic series of misunderstandings.

Ultimately, the short is remarkably wholesome. Bugs screws with the dim-witted vulture, but not in a particularly cruel way. In the end, they’re both quite kind to each other and I suppose that is part of the reason why this short endures after all these years.

This is the most complete and righteously angry, and yet most empathetic and appropriately measured essay on this topic I've read. Bravo.

Beautifully written! You inspired me to subscribe.