Who's Afraid of AI Art?

The new field of prompt-driven art generation is following the same cultural script as previous digital art innovations.

It seems like everyone is writing about artificial intelligence and art now, which makes me (the incurable contrarian) *not* want to write about it. But what is happening right now is simply too interesting to let pass without thinking about it out loud.

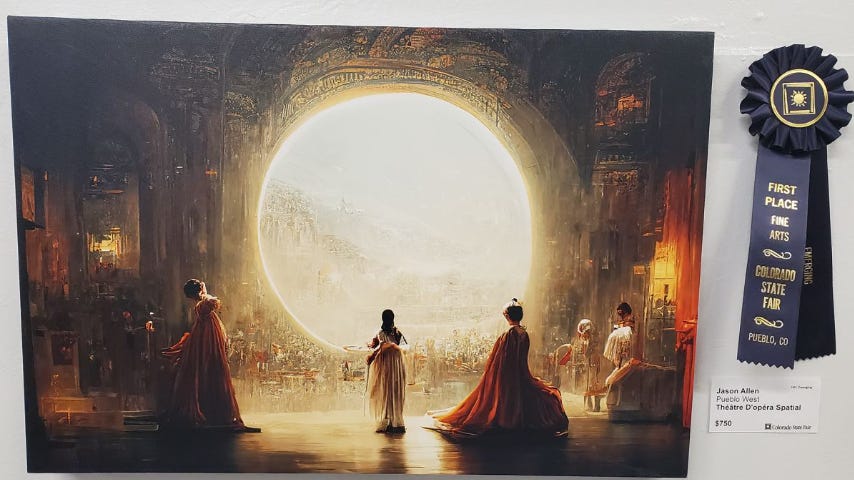

The trigger for this comes from the recent story in which a man won first place in an art show with an image produced through a text-to-image AI image generator. The image itself is pretty compelling, but the revelation that it was generated using an AI image generator has caused some people to cry “foul.”

I find this fascinating because I see in this story reflections of how artists have reacted when technology makes an intrusive entrance into an art form that had previously been considered the realm of human craftsmanship.

Using Computers Is Cheating

When it came out, Tron delivered to the movies a visual style never-before-seen. It was stark, unique, beautiful, unlike anything that had been seen before in its depiction of a digital fantasy world.

It was also snubbed for a visual effects nomination because the use of computers to render images for a movie was considered “cheating” in the larger field of visual effects.

Visual effects at the time were (if I may quote myself) “a menagerie of arts that encompassed painting, makeup, sculpture, modeling, robotics, material design, engineered camera work, and compositing multiple elements together for the final image.” Taking the hard work of these artists and “reducing” it to the rendered output of a computer program felt like a slap in the face to all the hard work of these dedicated artists.

This wasn’t the last time that artists would hold a grudge against computers. The Fellowship of the Ring was a gorgeous visual masterpiece, rightly deserving of its win for cinematography. After it won, cinematographers learned that the colors and lighting of the film were often enhanced in post-production instead of relying entirely on set lighting and traditional in-camera practices. They also considered this cheating, refusing to even nominate the other two Lord of the Rings films for that category.

But you ultimately cannot argue with or hold a grudge against results. Within 10 years of this snub, digital color alteration was ubiquitous in films and considered just another tool in the cinematographer’s bag.

Using computers is cheating… until everyone else in the industry learns how to use computers. Then it becomes part of the accepted process.

The Bleeding Edge of Digital Art

When people say that the image above is “cheating”, there are a lot of assumptions being brought to bear. The image was submitted into a category called “digital arts/digitally-manipulated photography.” When most people look at this category, they have an idea in their minds of what will go into the images that will be competing against one another. “Digital art” could be a series of photographs combined with procedurally rendered elements and hand-drawn components painstakingly composited into a perfect impossible image that combines photorealism with impressionism. Or it could be a generative algorithm that creates an image without any digital image manipulation tools.

But the core idea (in my opinion) is that the art show producers expect the human artist to be directly involved in creating the art on a rendering level. To this end, the expectation is that the artist had a direct hand in placing and generating all the elements

Ironically, this raises additional questions about the nature of digital art as a medium. Let’s look at that picture again and ask some of these questions

How direct does the artist have to be to create an image like this? Did he specify the color of the drapery on the right-hand edge? Did he create a text prompt that described this scene in enough detail that it generated the 5 (or 4? hard to tell) human characters we see and placed them as they are? What did the image generation give him “for free”? That is to say, what compositional elements here was he surprised to find? But the creators of generative art are often surprised with happy accidents that their algorithms produce, is there a certain threshold of surprise that makes art valid or invalid?

I enjoyed how this Penny Arcade comic cut to the bone on this issue. In this comic Tycho (blue shirt) is the wordsmith of the duo and Gabe (yellow shirt) is the artist. Through the years, there has always been tension between these two characters about the supremacy of art versus the written word.

The joke, of course, is how Tycho has always disdained his long-time artistic partner, viewing his contributions as an ancillary component to the core art of writing and how he is eager to replace his friend with a robot.

Creating images through a prompt-driven image generation system will become a powerful tool in the artist’s toolkit. But we should realize that these images still do not generate themselves. They are the process of what is likely to become an art of prompt generation. (For more on this, check out the first of Jon Stokes’ superb tutorial series on how AI content generation delivers images.)

When encountering new and exciting technologies, I have a history of being both generously optimistic and insufficiently visionary. I like exploring the possibilities of what is to come but I also want things to stay as they have been. This new world of AI content generation will evolve into something that is hard to envision, but we will adapt to it and develop new and exciting art with our robot friends.

Disney Shorts: Clock Cleaners (1937)

This is a lovely “Mickey, Donald, and Goofy work a job” short (which you can watch here), this time the trio are clock cleaners working to clean and maintain a humongous Big Ben-style city clock. This is a great one because we get all three charactesr in their element. Mickey is earnest and brave (if a bit clumsy), Donald gets himself into escalating trouble with his temper, and Goofy messes things up and causes trouble just by being Goofy.

The short starts out with some decent workman jokes and gags (and some really interesting sound design from a talking clock spring) but really kicks into high gear as Goofy becomes incapacitated through an altercation with the clock bell ringers and Mickey has to perform a series of death-defying stunts to keep Goofy from plummeting to his death.

The whole thing is funny, entertaining, and well-paced. It’s an excellent example of this genre of the early Disney cartoons and their obsession with finding subjects in all manner of workplaces.

The concern about it is AI replacing artists in many cases, but I'm more interested in seeing what artists do with AI assistance. I've already seen Ethan Nicolle play around with AI art quite a bit.

Absolutely fascinating. Feels like it was just yesterday rather than a decade ago that AI finally beat humans in Go, which in the early 00's I was pulling hard for team humanity and really believed that the complexity and simplicity of Go created some sort of asymptote-esque barrier that computers would never cross.

Now they beat us at art.

+1 for the Penny Arcade comic, hadn't read them in... also a decade apparently.