Visualizing Supreme Court Rulings

I’ve been trying very hard to keep this newsletter as much about COVID data and news as possible, but this week has seen the confirmation hearings for Judge Amy Coney Barrett and, while I don’t have very strong opinions about Judge Barrett or the manner in which she is being confirmed, I want to take this moment in time to talk about how I came to be divorced from the popular conception of a partisan Supreme Court.

This is the story of the data that broke me of that view.

The 5-4 Decisions

SCOTUS Background

How Do We Visualize SCOTUS Decisions?

Disney Shorts: Pigs is Pigs

There is this persistent idea that the Supreme Court has consisted of a 5-4 conservative majority for about 20 years, with the five justices appointed by a Republican presidents and 4 appointed by Democratic presidents. Two years ago, I decided to try download data to visualize the partisanship of the court and this is the story of how I felt like the narrative I’ve always heard was so very different from what I saw.

As a point against me, I’m stepping into an arena in which I am not an expert. I’m not a lawyer and, while I enjoy reading SCOTUS decisions and I *really* enjoy listening to oral arguments, the legal details can often go over my head. I don’t like to talk about something when I’m uncertain about it and I will admit that I’m not certain what story my review of the data really tells. I just know that it’s not a clean and clear story of blinkered partisanship that I’d previously accepted.

The 5-4 Decisions

I was inspired to dig into this data due to a tweet from Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s who has been using the 5-4 decision as a rallying point against the Robert’s Court. I think this is the tweet that inspired my data dive.

To see that 73 cases have been decided by a clean “conservative vs liberal” partisan split seems pretty damning to a court that is meant to be non-partisan. So, me being who I am, I wanted to verify that this was even correct.

First, however, a little background for anyone who is not quite so familiar with the Supreme Court.

SCOTUS Background

SCOTUS (the Supreme Court Of The United States) is made of 9 appointed justices. John Roberts was confirmed as Chief Justice in 2005, which means that the Supreme Court has been the “Roberts Court” since September 2005. If we are casting justices as “conservative” or “liberal”, then the justices who have served during the Roberts Court would fall into the following categories.

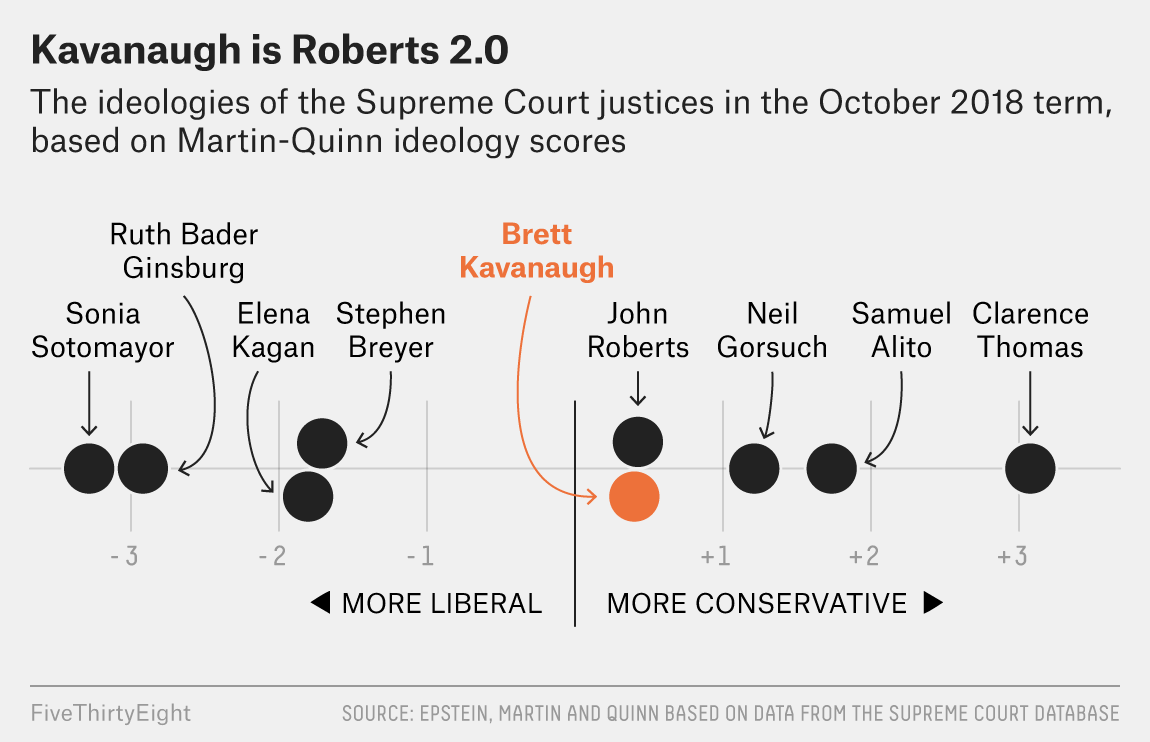

There is a lot of argument about “how liberal” or “how conservative” these justices might be and you may have seen these kinds of visuals that try to quantify ruling results into a “left vs right” line.

This idea of locating these justices on a one dimensional partisanship line is extremely compelling because it is simple. This particular measurement is based on a proposed partisanship measurement from a 2016 political science paper and it has been enormously successful at the main goal of such papers, which is to get people to talk about them and get journalists to use them for explainer articles in the New York Times.

I was fairly skeptical of this presentation simply because it was so incredibly simplistic, boiling a justice’s writings on complex legal matters to a “conservative v liberal” metric. But it draws from the Supreme Court Database, which was a good place for me to start as I was investigating Senator Whitehouse’s claims of the 5-4 partisan split.

How Do We Visualize SCOTUS Decisions?

The reason I write this visualization 18 months ago and never published it is in no small part because it was so damned complex to try to parse the results in a way that showed partisanship.

I started with the easy cases. If all the “conservatives” were on one side and all the “liberals” were on the other, that was a “typical partisan split”. And if the case was decided unanimously, that’s also easy to categorize.

But what if it was 5-4 with 4 liberals and a conservative justice? But it could also be 5-4 with the liberal bloc and the conservative bloc split. Georgia v Public.Resource.Org was decided with 3 conservatives and 2 liberals in the majority and 2 of each in the minority. Should I try to distinguish between 5-4 cases with a swing justice and 5-4 cases with a very mixed set?

In the end, I came up with this very simplistic yet still overly confusing color scheme to try to group cases simply by which justices voted together.

If justices were indeed “liberal” or “conservative” in this one-dimensional way, then we would expect that decisions would fall along that same metric. For example, if a decision is a -2 liberal, we should expect expect Sotomayor and Ginsburg to be in the dissent and all the other justices in the majority.

This is not what we find at all.

Note: This visual is from an interactive application I wrote. The big numbers you see are the vote counts and the smaller footer numbers are the month-year of the decision. The annoying gray boxes are the 4-4 decisions from the time when Mitch McConnell decided to mess with my beautiful visualization by allowing only 8 justices on the court for months.

First of all, let’s make it clear that the most common SCOTUS result by far is the unanimous ruling. Of the 1100+ cases that have been decided since 2005, all the justices came to the same conclusion on 531 (46%) of them. Even more interesting to me is that an “atypical bipartisan” 5-4 split was more common than a “typical partisan” 5-4 split.

This is where I actually do like my method for splitting up the cases, because we see that Senator Whitehouse’s implication that we are in a crisis of constant 5-4 conservative vs liberal split decisions is quite some distance from what we see in practice.

If you’re still a proponent of the “left-v-right” narrative on the Supreme Court, it gets even weirder when you look at the composition of some of the atypical 5-4 splits. The aforementioned Georgia v Public.Resource.Org decision saw Ginsburg (the “most liberal” justice) pair with Thomas and Alito (the two “most conservative” justices), though Ginsburg did write a separate opinion. But also there are cases such as Mont v United States where Ginsburg was the deciding vote with the “conservative” majority and joined Thomas’ opinion.

This kind of mix-and-match of justices and “line-crossing” happens ALL THE TIME. We tend to get so fixated on a half-dozen high-profile cases that we don’t really notice that the Supreme Court is an very fluid group of justices who work together a lot and commonly convince each other to vote one way or another on a wide variety of cases.

This makes it much harder for me to have a really strong opinion on the “liberal v conservative” fight over the Supreme Court. I recognize that different justices have a tendency toward one “side” or another, often very broadly in line with the “team” that nominated them to the bench. But the closer I look at the court, the more it looks like a team of individuals talking and thinking and working to perform what they believe is justice by the law. Perhaps it is a bit naïve but I see the Supreme Court as the only branch of government I genuinely still admire.

Disney Shorts: Pigs is Pigs

Though the quality of the Disney shorts kind of took a bit of a downturn in the 40’s and 50’s, there are a few that stand out in part simply because the animators still liked to experiment from time to time. This was an era when the Disney shorts were struggling against the less elegant but more zany and untethered Warner Bros Looney Tunes shorts. Many animators at Disney were jealous of the wide berth WB seemed to give animators to explore crazier concepts.

Pigs is Pigs is an absolutely delightful break from the Disney style. The character visual style is much more flat and angular, but in a style that is very modern (for the time). The story is a pile of hilarity, a story about how an argument about a 4 cent rate disagreement with a customer and a blind adherence to the rules becomes a bureaucratic nightmare that nearly destroys a multi-million dollar company.

It’s a wonderful morality tale about customer service with delightful music that also managed to really fit within its visual style.

Also worth noting how principles Supreme Court decisions tend to be. Congress and the President tend to use whatever excuse is handy to reach their desired policy. But in the Supreme Court, all of the "liberal" justices will agree that the Federal government can outlaw personal use marijuana because they believe the Federal government has that power, while only conservatives dissent in favor of the pot growers. Maybe the principles favor "liberal" or "conservative" policies best overall, but looking at the results of cases misses the point unless you take the principles as seriously as the justices do.

Great Work on the Supreme Court analysis. At the moment all the justices are serious people who take the law seriously with the possible exception of Sotomayer who seems overly results oriented. Also John Roberts occasionally seems more interested in policy than law but he's definitely serious. Amy Cony Barrett seems like a fine addition given her demonstrated temperament and knowledge as demonstrated in her hearing. One of the reasons I will not vote for Biden is his turning the judicial confirmation hearings into goat rodeos like the Bork and Thomas hearings he presided over.