The Role Of The Non-Expert Specialist, Part 2

What went wrong in journalism and how the free market is fixing it

This is the second part of a 2 part series on why so much good information in this crisis has come from non-official, non-expert sources and how to develop a sense of what is good information and a sense of skepticism for incomplete or partial information.

The Ruling Class and The Scribes

Why Listen to the Non-Expert Specialist?

Where Does Expertise Come From?

Guidelines for the Non-Expert Specialist

Looney Tunes: Water, Water, Every Hare

The Ruling Class and The Scribes

When I started writing the second installment of this series, I assumed I would just move straight into describing how I realized could find good information that had not crossed the threshold of common knowledge. But events in the last week made me realize that there is another component to the problem, a bridge over which faulty information must pass from the institutional sources to the general public. This bridge is “the press”.

“The press” is somewhat hard to define. Is Fox News “the press”? Well, yes. So is CNN, Vox, MSNBC, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. When trying to hone in on the type of writers and information disseminators who I think are part of “the problem”, my ire falls on the incurious generalist.

The incurious generalist is the kind of purveyor of information who takes something he or she heard and passes it along without critical judgement, careful thought, or investigation. This person writes about every topic that falls before them, from sports to economic policies to pandemic procedures to constitutional law to academics or science or psychology or international politics.

This type of pundit tends to seek out an authority figure for a short quote to make a quick point and then moves along to the next issue. There is very rarely reflection, probing questions, or critical thinking on a given topic. The pundit is an information conduit, not an investigative participant.

Back in April, I wrote an article entitled Stenographers for the Elite and that title is enough of an explanation of my opinion on critical thinking in journalism that you hardly need to read the full article. They are disinclined to investigate complexity, lacking the base subject knowledge to ask the questions that might lead to greater understanding in this subject among their readers. They largely regurgitate what they have been told with what they judge to be the appropriate amount of panic, outrage, or skepticism.

Part of the problem is the incurious nature of these writers. But it might be that there is a bigger problem: Journalism has for too long been the realm of the scoop and the dunk, a realm of trickery and mockery rather than a place where a thoughtful person could trust that their nuanced and complex information will be fairly represented.

Since I wrote the first installment of this short series, events have overtaken me. Specifically, Scott Alexander (who wrote the epic masks post I referenced in my last piece) has been writing about what he calls “Legible Expertise”. If you’re looking for someone who thinks harder than I do and is kinder to people than I am and you don’t mind reading tens of thousands of words per week, Scott’s your guy.

Scott has been thinking a lot about journalism and expertise and he heard from a journalist about why what we read in the press ends up falling so short of meaningful reality:

In most journalistic settings, you can't just write "here's what I think". You have to write "here's what my source, a recognized expert, said when I interviewed them". And the experts are pretty sparing with their interviews for contrarian stories.

The way my correspondent described it: sources don't usually get to approve the way they're quoted in an article, or to see it before it gets published. So they're really cagey about saying anything that might get misinterpreted. Maybe their real opinion is that X is a hard question, there are good points on both sides, but overall they think it probably isn't true. But if a reporter wants to write "X Is Dumb And All Epidemiologists Are Idiots For Believing It", they can slice and dice your interview until your cautiously-skeptical-of-X statement sounds like you're backing them up. So experts end up paranoid about saying potentially-controversial-sounding things to reporters.

The long story short here is that experts don’t trust journalists to get things right. They don’t trust them to understand or communicate nuance, they don’t trust them to a point where they can speak off-the-cuff. The experts don’t believe they can have a conversation with a reporter in a way that allows them to dig into the details, to work through a problem, to speak in their own voice.

And, to be honest, why should they?

A significant chunk of journalism has become addicted to dunking or (as Glenn Greenwald put it) tattling on their sources. The general perspective of the public is that journalists are not out to inform the public, but out for blood. The entire reason Scott Alexander now writes on SubStack instead of his self-hosted blog is because he became convinced that a set of New York Times reporters were threatening to dox him for… writing a helpful article about the efficacy of masks.

The actions of reporters over the last decade has been to find someone out there, dig up dirt on them, and destroy them. That is why they are left regurgitating press releases written by committees. But that’s not where the interesting stories are. By the time the information gets through the public health committee and out of the mouths of official sources on cable TV, it’s already several weeks old.

So where do we go for fresh information?

Why Listen to the Non-Expert Specialist ?

I think that there is a real role for a person who is dedicated to the task of sorting through all the difficult details of a topic and tries to take a very serious truth-oriented view of what is going on. I call this person the Non-Expert Specialist because they are a person who is not necessarily an expert in the topic at hand but has decided for whatever reason to come from the realm of the “normal people” to educate themselves, listen to experts, sift through information, read, think, consider, and communicate their views to others.

A lot of the people I’ve grown to trust over this pandemic are non-expert specialists. Kelley K isn’t an epidemiologist, but she follows Georgia COVID data so closely, there isn’t a single journalist in the field who can match her detailed knowledge. Alicia Smith does not (to my knowledge) have a degree math or science, but she has dedicated herself to a careful study of this pandemic and I would trust her over most official announcements. Lyman Stone has developed an relatively recent expertise on CDC reporting on excess deaths. Youyang Gu is a data scientists who makes excellent COVID-19 projections.

Something strange has happened in this pandemic in which people we would never have given a second though to on this topic 18 months ago have become go-to resources for vital information.

How did this happen?

Let me answer this with a story: back in May, when this was all still in the early stages and context was scarce, Washington state (where I live) issued a set of guidelines that said we could only move to the next phase of re-opening with “near-zero incidence” of COVID-19 infection in the community.

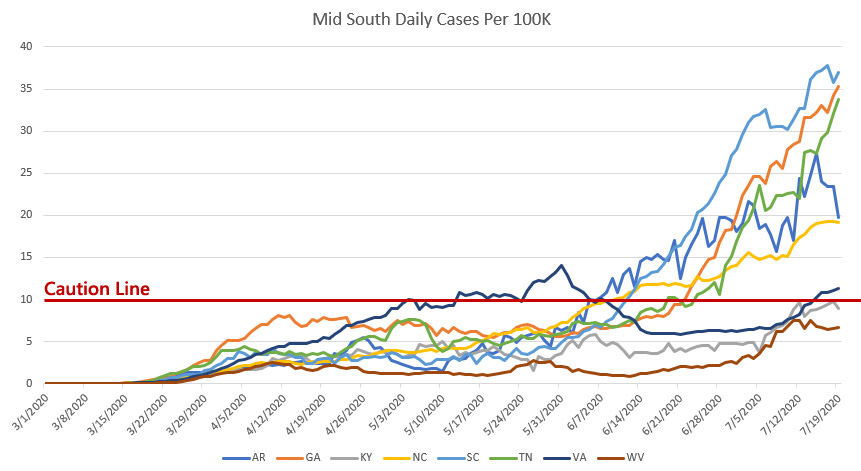

This vision of re-opening was born from the idea that we could self-isolate to such a level that we could more-or-less eradicate the disease within a community. I was skeptical at the time that this was the correct measurement and, two months later, I published my first “all the states COVID numbers” post in which I suggested a “caution line” of 10 new cases per 100K residents per day.

This was a number that I kept seeing as a something of a tipping point. A region may go above 10 cases per day and things might come back down, but we needed to be vigilant because if they went over 10 cases per day and then started accelerating, we could get quickly see things get very bad very fast.

The caution line was nothing more than me eye-balling the data and watching things happen. But I knew that the “near-zero incidence” of 0.8 cases per day was horribly unrealistic and betrayed that the official guidance didn’t seem to understand what was going on practically in this pandemic.

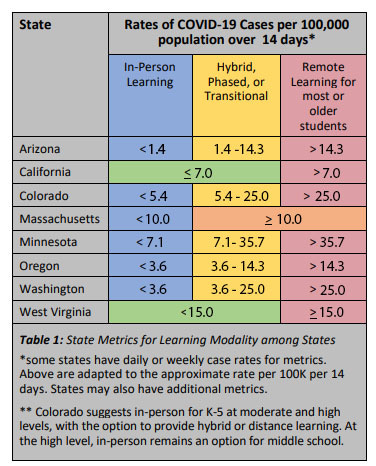

Here we are, 9 months later, and where is the official guidance? Well, to start, no one is talking about near-zero incidence. That is clearly not something we can hope for, possibly not even after vaccines are widespread. But the metrics have changed across the board. Here is the official school return metric guidance for 8 states.

If we translate that from “over 14 days” to my ad hoc “per day” suggestion, we get this chart:

This was, quite frankly, astonishing to me. In 9 months, the official guidance moved from “we can only open when we have eradicated this virus” to “the suggestion made by this anonymous weirdo who is eye-balling infection charts is more or less what we have, upon months of reflection, decided is acceptable”.

Again, not trying to toot my own horn here (ew) but it’s incredibly strange to describe exactly how weird this experience is. The caution line I’ve been using for months has ended up very close to the official guidance in many states. My gut-level estimates were much closer to a realistic goal than what the experts at my state health department put out.

And this has happened over and over again.

Should we open playgrounds? Of course we should, no rational person would suggest otherwise. It took my state 5 months to figure this out.

What about going back to school? The risks are quite low and have been since we’ve started trying to measure this.

Do holiday gatherings cause massive COVID spread? Despite the fact that we’re constantly warned that they will, it doesn’t seem to be the case.

Are vaccine roll-outs a failure or a success? Well, if we look strictly at the data, things seem to be going pretty well.

I discovered very little of this information on my own. The vast majority of it was gleaned by carefully watching trusted sources with real expertise.

Which leads to the question:

Where Does the Expertise Come From?

Almost none of the information I talk about here comes from my own expertise. I have found myself in the peculiar position of being able to find other experts who are deep in their field but also willing to answer questions or help others understand what is going on.

These experts are actually much easier to find than you might suspect. But you have to know what to look for.

1) they stay in their lane

I follow a few dozen people who I trust with various topics and for the most part they stick to their topics. Trevor Bedford is a virologist & has very few opinions on opening schools. Alina Chan (scientist-turned-detective) has been documenting China’s role in this pandemic but does claim authoritative expertise on vaccine development. Derek Lowe does astounding writing on vaccine development but if you read him, you’re gonna need to care a lot about the pharmaceutical industry and vaccine development because that is basically all he talks about.

This isn’t even so much about not having other opinions about things. This is about the fact that experts who know one topic understand they are *not* experts in another. They have confidence in their field because they know their stuff but they also show a lot less confidence when they are reaching outside their area of expertise.

2) they are comfortable with ambiguity

There are a few microbiologists I know who are funny and engaging and they highlight the stuff that everyone in their field knows to be true. But they also talk about stuff that they wonder about. They say “I don’t know” a lot. They don’t rip on people for asking questions or not knowing things. When something is well known, they say so. When it’s still under investigation, they show a cautious curiosity. They don’t jump to conclusions.

3) new information follows patterns, but not narratives

Among the experts I follow, new information follows a pattern. When I wrote about why it might make sense to delay the second dose of the COVID vaccine, that wasn’t information that exists in a vacuum. Experts in vaccinology have looked at a lot of vaccines over the years and they have seen patterns and expected those patterns to hold true in the future. There’s a lot of expertise floating around out there that doesn’t quite make it to what Nate Silver calls the “high prestige news outlets”

Of course, the only way to really know if someone is an expert is over time. There are people I trust on certain topics, but I also trust the people they trust. That trust has been borne out pretty frequently but it is also frequently accompanied by explanations. These experts don’t just know *how* the thing is happening. They know *why* the thing is happening and can explain it to others.

Guidelines for the Non-Expert Specialist

I’m not an expert in any of these fields. But, like Nate, I’m an obsessive follower of experts. I read a lot of books and papers. I prefer to download and look at the data itself rather than skim a dashboard. Diving deep into the topic is interesting to me. I love learning new things and asking practical questions that fill in my gaps of knowledge.

It turns out this is a pretty common skill set for the people who become a central hub for a lot of disparate information. Of all the people I know who so this, these are their most common traits and the following would be my advice for anyone who wants to become a information hub for a particular topic.

1) get comfortable digesting expert information

Almost none of the information I share comes from me. This was why, when I explained that I’m 90% sure that vaccinations reduce COVID transmission, I titled it “Losing My Mind”. I try not to go too far off the rails in proposing my own theories b/c there’s a lot of stuff in this field that I don’t know. I’m much more comfortable finding expertise from other people, thinking about it, and presenting it here.

I’m not a virologist, but I’m familiar with genetics enough to know that, when we’re tracing the origin of the virus, I should go look at what Trevor Bedford, a virologist specializing in viral evolution, has to say. Lo and behold, he has a lot to say about it.

Since this started, I’ve been collecting lists of people who I think are careful, thoughtful, good at explaining things, and live and work deep within their field. They are my first-round filter for important information. I’m less of an expert in anything at all and more of a conduit for their expertise.

2) ask more questions than you answer

Every event that you read about in a newspaper has a massive history behind it. There are books worth of details to almost any event big enough to make it into a major news story.

The most valuable thing that happens in my head is asking questions that fill in the gaps in a story. Let’s take vaccine distribution as an example. There were many stories about the failure of vaccine administration, but I never got a clear picture of how vaccine distribution actually worked.

I saw a viral video of trucks leaving the Pfizer plant with people cheering along the road. Where were those trucks going? Do we store those vaccines in a federally owned warehouse? Who moves them from the truck to the warehouse? Or do they go immediately onto other trucks headed toward various states? Does the state health department hold the vaccines until the hospital needs them? How does a hospital communicate their need for more vaccines? Is this a recently developed digital communication solution? Or is this something a large-scale medical software company like Epic managed to put together in a few short months? How did they do that? I’ve worked for medical software companies and a few months is an insanely small amount of time to put together a new feature and test it across hospital and distribution endpoints. Did they have to cut corners to do this? What corners?

If you think hard enough about how stuff works, if you ask about every step along the path of any endeavor, you can dig down into the details to an almost infinite degree. One wonderful thing I’ve discovered is that people who do the hard work of actually making things run properly really enjoy telling others about the amount of work it takes to really make things run properly. They do hard jobs and no one ever asks about the details.

The going assumption among many people (and, embarrassingly, most journalists) is that of course everything should always run smoothly, why would it not? If it isn’t running smoothly, it is because there is a scandal somewhere. But the simple maintenance of nearly everything in our lives is an enormous endeavor involving thousands if not millions of people making sure that the guy is there to run the forklift to unload the vaccine crates and put them into cold storage fast enough that they don’t go bad.

That guy running the forklift has a name. He’s got a history. He’s got an interesting story about how he got that job running a forklift, moving piles of vials from one place to another that will end up saving thousands of lives.

You can dig down into these stories if you ask the right questions. All it takes is the desire to ask the questions to fill in the gaps of how things work and the willingness to say “I don’t know” when you reach the limits of your investigation. Not only is that the truth, but people recognize the limits of investigation and respect that. No one expects a single person to be able to know everything or talk to everyone. When you write about a topic, recognize when you’ve hit the limits of your knowledge and invite the reader to move forward where you left off.

3) don’t take any answer at face value

This is less about saying “people are lying to you” and more an exhortation that every answer you get is going to be loaded with caveats or knowledge assumptions. Most experts I’ve come across do their best to answer honest questions. They really do want to inform, educate, and help curious and honest people come to a better place of understanding.

Nevertheless, every answer comes with caveats and presuppositions. Don’t be afraid to push into those questions. The real experts will be glad someone cares enough to dig deeper while the fake experts will be annoyed that someone didn’t take their word for it.

And In Conclusion

I believe that we’re on the very edge of an information revolution. There is an accelerating collapse of trust in institutional structures and an increasing interest in Smart People Who Think Hard.

As it is, my trust lies in people who are free of editorial control. I read Normcore Tech for technology, machine learning, and tech ethics info. I read Zero Credibility for start-up info and updates on decentralized networking. I read Glenn Greenwald for media news and Emily Oster for school COVID news and parental science.

I read Razib Khan for (this is a quote when I asked him to describe his substack) “science and data journalism i guess?”

The lines are blurring. We’re moving past a world in which our newspaper has sections on culture and science and art and politics and we restrict our opinions to those segments. I believe we’re shifting to a world in which trust is the primary currency and everything flows down from that.

Do you trust this person to be honest with you? Glenn Greenwald and Matthew Yglesias both quit their jobs within a stable and profitable news organization in order to speak freely without an editor. That may very well be the future of information dissemination.

The old world of gate-keeper journalism is crumbling and there is a lot of room in this new world for honest brokers who prove themselves over time to an audience who understands context and nuance.

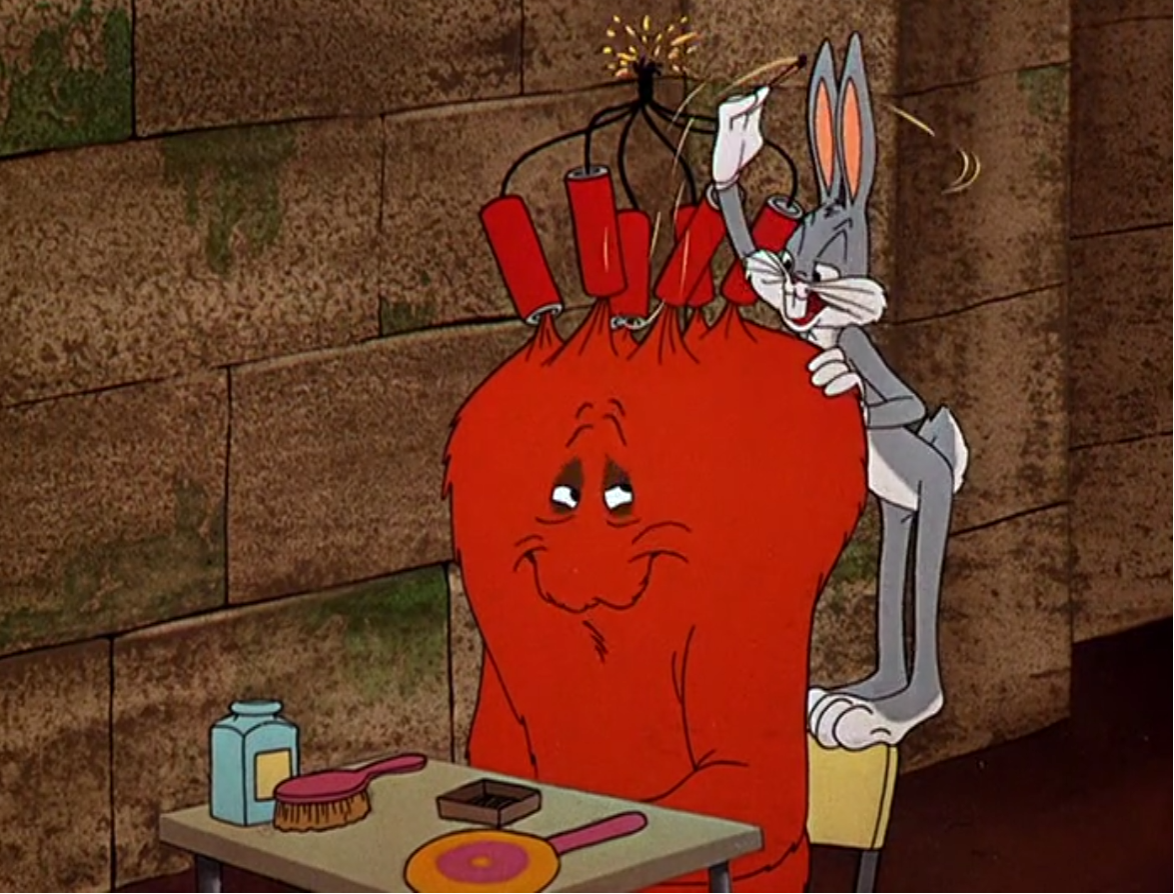

Looney Tunes: Water Water Every Hare

This is one of those shorts that starts out with a pile of inventive gags and just never lets up. We start with Bugs’ rabbit hole flooding, floating bugs down a river to where a mad scientist can abduct him for nefarious purposes.

Upon Bugs’ escape, the evil scientist enlists Gossamer (first seen 6 years previous in Hair-Raising Hare) to track Bugs down. This results, of course, in Gossamer being repeatedly tricked by Bugs until he literally quits the short and the battle shifts back between Bugs and the scientist.

This is an odd one to review. It’s a solid cartoon in its own right, but something about it feels like we’ve run around this concept once before and have discovered few new things. It’s funny enough, but not inventive enough.

I think this may be the best thing you have written - at least for me. I have found your thinking, first on Twitter, then through here, to be invaluable in helping me to stop and reframe my own assumptions and understanding of many things. In this article you truly encapsulate why that is the case: honesty, curiosity, willingness to admit mistakes, all in the pursuit of knowing something worthwhile. I do hope that framework becomes more popular.

Great piece!

Reminds me of the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect, observed by physicist Murray Gell-Mann and summarized by Michael Crichton:

‘...the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. ... You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. ...

‘In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate .... You turn the page, and forget what you know.”