The Gas Stove Debate & How Science Has Become a Political Strategy

Recent studies touting the dangers of gas stoves are part of a political playbook that weaponizes regulatory agencies to achieve political goals.

It’s amazing to watch how the gas stove debate has exploded over the last week. As I watched the arguments unfold, I realized that this is a nearly perfect example of the blueprint of policy advocacy that relies on an appeal to technocratic health policy as a means of bypassing any form of representative government. This entire narrative started as a naked appeal to unaccountable and unelected regulatory figures to make the policies that legislators are too frightened to vote on.

But it also provided an exceptional example of how the authority crisis is impacting this discussion and how distrust of previously non-partisan sources of information is disrupting the intended pathway for advancing these policies.

It’s hard to say where exactly the story started because the groundwork for eliminating gas stoves has been in the policy pipeline for a few years. The Washington Post was writing about it a year ago, citing a meta-study (a study collecting and estimating the data from other studies) that claimed gas stoves increased rates of childhood asthma by 42% and noting that:

gas bans have spread from liberal enclaves in California to bigger cities across the country, including Boston, Denver and Seattle. Last week, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed the first statewide gas ban by 2027, a move that climate activists cheered while calling for a faster timeline.

At the time, the narrative of the article was primarily pitting climate activists against gas industry lobbyists, but all the actual policy movement was happening in very blue states or municipalities.

What really kicked this controversy into high gear was the statement from US Consumer Product Safety Commission CPSC Commissioner Richard Trumka:

We need to be talking about regulating gas stoves, whether that is drastically improving emissions or banning gas stoves entirely. And I think we out to keep that possibility of a ban in mind, because it’s a powerful tool in our tool belt and it’s a real possibility here.

These health concerns were given fresh life with a new meta-study that said that 12.7% of childhood asthma in the US is due to gas stoves. Interestingly, two of the authors of this study work for Rocky Mountain Institute, a non-profit that advocates for removing all non-electrical appliances and partners with companies to remove gas lines from buildings and build electric-only buildings.

A Battle of Trust

This started something of a battle of trust. When I heard about that study, I expressed some skepticism about this number for a few reasons.

First, gas appliances are far more common in higher-income households than in low-income households.

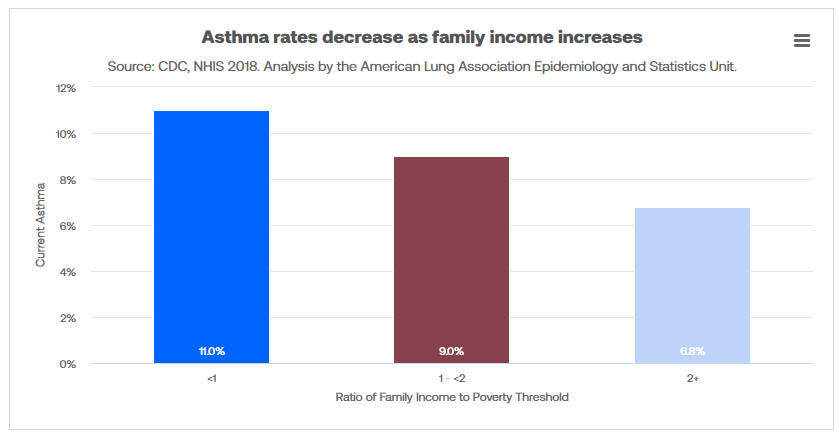

And yet childhood asthma is almost twice as common in low-income households.

The second reason for skepticism is that gas stoves are much more common in the west and northeast and not nearly as common in the south.

And yet childhood asthma rates are lower in the west and midwest and high in the south and northeast.

These were just a few things I was vaguely aware of that made me look askance at this very large effect. It seemed that this study was enough for people to say with utter confidence that gas stoves are such a huge driver of childhood asthma that is in the interest of population-wide public health to use regulatory and consumer protection bureaucracies to remove this risk. And yet a quick check on these effects doesn’t seem to hold up for population-wide impacts.

Indeed, as the story trundled along, the debate seemed to be splitting into two groups. The first group is people who took this study at face value as gospel truth and wanted to move immediately to implement policies on this suddenly common knowledge. I liked how Charles CW Cooke put it: Update patch 1.5.205 was installed successfully.

The second group was filled with people who simply dismissed this new information or went in search of alternative sources to try to bring more information to the table to make sense of this. One of the best reviews of this study (and the 2013 study and along with several additional sources) came from Emily Oster, who concluded that it’s really hard to say if gas stoves are a big safety concern for in-home air pollution or if there are confounding effects that muddle the data.

As with most of her work, Oster’s review is excellent but the reason many people went to her with this question is that they trust her to just be honest with them. She has demonstrated a commitment to data and a critical eye toward studies that is entirely lacking with most news sources.

If you’re interested in another critical eye toward these studies, I recommend this thread from Steve Everley. In it, he notes that

the largest analysis of gas stoves and asthma found no evidence of association between the two

much of the emissions being attributed to the stove may be coming from the food being cooked

the most dire measurements of gas stoves have come from studies that measure emissions in a hermetically sealed condition with no ventilation whatsoever

The end result of all this is that we have competing sets of data drawing competing conclusions and people picking which conclusion they are going to move forward with largely based on tribal affiliation.

It’s ultimately a good thing that a loss of trust in the core science is disrupting the playbook for bypassing a political process with a regulatory one. But it’s worth remembering that this is a very intentional process. Studies are done with the goal of weaponizing them to achieve political ends under the fig leaves of science and safety. This is a real shame because there is little room for compromise if one side thinks the other is simply denying the plain reality of science.

The Bigger Question

All of this debate is over the narrow question of “how safe is a gas stove,” which is a question that has an answer and yes, sure, we should seek more knowledge to better answer that question.

But I’m more concerned with a bigger concern, which is that I think everyone should be able to make their own calculus on safety versus life. Aiming for a maximally safe society should not actually be an end goal. I should be able to look at the risks of a gas stove and say, “You know what? For me and for my family, we’re ok with that risk.”

When asking policy questions, be they around COVID or gas stoves, the answer “because I want to” isn’t given nearly enough weight. That’s a good reason for most things and it should be more broadly respected.

We shouldn’t feel the need to submit a four-page essay explaining every preference. This is the beauty of a free society, that we can make our decisions based entirely on our own subjective and unexplained desires. Some people will decide the risks are too high and move to an inductive stove and God bless them. Others prefer the cooking experience of gas and they don’t have to tell us why. They can just like it because they do.

There is something that sticks in my craw when people start appealing to regulators to make sure everyone makes the “right” choices. It’s a rejection of the variety and diversity of experiences and preferences that makes life interesting.

It also re-awakens the libertarian in me. So what if my fire alarm goes off when I’m searing my steak? I know exactly what I’m doing and I want to do it. I know the risks and happily accept them with a side of greens and a rich red wine. I want gas stoves, electric stoves, induction stoves, wood-fired brick ovens, grills, smokers, campfires, bonfires, and air fryers. I want people to heat food a hundred different ways and discover the pros and cons of all of them. And I want them to do this without someone looking over their shoulder and telling them what air to breathe.

Disney Shorts: Two-Gun Mickey (1934)

This is a wild ride. Minnie is a pioneer out to make her way in the old west and Mickey is introduced as a dismissive and rude cowpoke who doesn't give her the respect she deserves.

When Minnie takes out a big old bag of money from the town bank (why?!? To what end or purpose?) she attracts the attention of the villainous Peg Leg Pete who 1) hilariously has a spur on his peg leg 2) is inexplicably coded as Mexican.

Pete gives chase his small army of identical ne'er do wells and Minnie is in great peril until Mickey comes to the rescue.

This short is best seen as a parody of the popular rescue melodramas of the time. Mickey is the perfect cartoon protagonist as someone who is alternately a western superhero and a comic buffoon depending entirely on which will get the biggest laugh.

The thing I was yelling from the rooftop during Covid was that they were using the pandemic to expand government policy and “rules,” in the name of a public health emergency. At the very same time they were running daily death counts for Covid, they quietly opened a climate office in HHS.

Now, they have precedent to do all sorts of fun things, not the least of which is circumvent state legislatures to change voting laws.

I completely agree with you (and I also happen to like gas cooking, and my propane barbecue) but you probably need to at least nod to externalities on things like campfires, which are (I assume) not inside your house.