The Fetterman Tipping Point

The Fetterman, Oz debate leads us to to ask why journalists continue to sacrifice truth for partisanship

Every once in a while, there is an event that runs so counter to a media narrative that it generates a shocking breach of trust between media figures and the public. This doesn’t happen terribly often; we are much more used to the long-standing erosion of trust that comes through a steady drip of poor information or partisan nudging. But there are certain moments where the narrative runs into the brick wall of reality so shockingly that we have to choose between the narrative and our own eyes.

A good example of this was the Rathergate controversy in which Dan Rather used forged documents as evidence in a national news hit on then-President George W Bush. The evidence against Rather was so plain, it took only a single image for everyone to see that they had been lied to.

I believe the debate between John Fetterman and Mehmet Oz was such an event. The common knowledge and media narrative going into that debate were so out of line with what the viewers saw that it shattered months of narrative building and, with it, the remaining grace and trust the public was willing to give to the media.

The nature of the Fetterman narrative was a perfect storm for media trust because it represented such a unique moment when trust in third-party reporters was truly necessary—accept no substitutes. Rather than use this opportunity to build trust, the majority of media members who were in a position to inform the public chose instead to tell a useless lie in order to play along with preferred narrative of the Fetterman campaign.

Philosophy of Journalism 101

The entire reason that journalism exists is that most of us don’t have time to discover, filter, and digest new information about the world and we need someone we can trust to do this for us.

A simple example of this is the monthly employment report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Last months’ report was 1800 words long and walks through the number of people employed and unemployed as counted through both the household survey and the establishment survey, split across six demographics, diving into how jobs have grown across a dozen industries.

A journalist reporting on markets and the economy would

know when the report comes out (8:30 AM EST on the first Friday of every month)

know what parts of the report are most important and relevant

be able to write about this for a layman, giving historic context and connecting it to the state of the economy as a whole

This is the mildest form of expertise, something that can be absorbed with a week or so of study. But most people don’t have a week to do that. They don’t have the time to understand the context of this report. They trust a journalist to absorb this background info and help them sift through the details.

The crisis of trust in journalism has to do with the fact that so many people simply don’t trust journalists to give them a clean expression of the facts. We expect reporting to come to us incomplete. We expect it to have a slant. We expect that, when we investigate the question ourselves, we will discover important context that has been conveniently left out. We expect that we will be misled.

This expectation has seeped into every form of reporting, from political reporting to economics, crime, entertainment, and public health. We expect the entire endeavor of journalism to be tainted.

But even with these low expectations, we still can’t put our own two eyes on every event that occurs. We can’t be everywhere, observing every event to render our own individual judgements.

The Need For Trustworthy Eyes

This is how the tension first began in the Fetterman story. With most stories, we don’t need first-hand experience to understand the topic being presented to us in the media. We can read a report or read a book on the topic or look at the data or go to the physical location and see for ourselves. But the question of John Fetterman’s health wasn’t like that. There was no report to read, no data to assess. In order to understand Fetterman’s condition, we needed to see it for ourselves.

When it comes to assessing the medical condition of a candidate, most Americans are incredibly conservative. There is a strain of laudable grace that we want to give to someone who is recovering from an injury. We understand they need time to breathe, space to recover. We don’t want to push on them or jump to conclusions.

That is where Fetterman’s stroke thrust us into a conundrum. When it comes to assessing someone’s mental health, there is no shortcut. You simply need to see it for yourself. There is no substitute for sitting down with someone for a few hours and getting a sense of how they are doing. We don’t trust news clips, they’re too short and can be taken out of context by partisans who will spin even the most cogent candidate as an idiot. We don’t trust snippets or blurbs. This is information that must be gathered first-hand in a long-form observation.

In this, we were necessarily dependent on the reporters that we’ve grown to distrust. There was simply no way around it. We can’t trust video clips and we don’t have time or access with this man to self-assess, we must rely on what is reported about his condition.

Leading up to the debate, the reports were uniformly positive. For months, every reporter who spent enough time with Fetterman to assess his mental state told us that he might be struggling with the offhand word but he was overall fit for office. We had little choice but to trust them because we had no compelling experience or evidence to contradict this position.

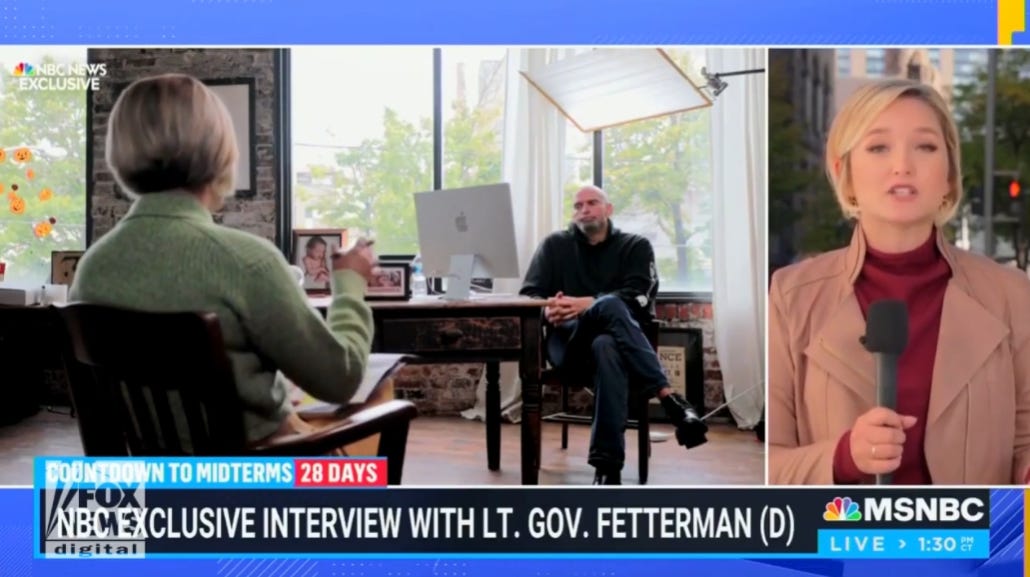

In early October, NBC reporter Dasha Burns discussed her experiences talking with Fetterman before and after his stroke and suggested that Fetterman was struggling to understand spoken conversations.

Her comments on Fetterman’s condition were so mild that to call them a criticism is to admit that you didn’t actually watch her discussing her experience. She was almost apologetic as she tried to convey to her audience the truth of what she heard and saw as she interviewed Fetterman. It was a 60 second assessment that clearly aimed as nothing more than trying to communicate the reality of what she saw.

For this professional faux pas, Burns was attacked not only by the Fetterman campaign (expected) but by other journalists (yikes) who implied that she was some combination of a liar and a bigot. Not only did the news of Fetterman’s condition seem always on the bright side, any dissenting opinion was not just ignored but punished.

There is a question, especially among some left-leaning observers about why Fetterman didn’t simply refuse the debate. He could have kept up this strategy of staying out of sight. By refusing to debate he could have avoided this scrutiny and likely won Pennsylvania without ever presenting himself to the unforgiving eye of the public. Why would he do this?

I have no answer but my own speculation. The only vision I can propose is that the Fetterman team believed what was being written about them. I try to place myself in the room as the discussion plays out and my mind concocts this scenario:

Fetterman Team (nervous about the conversation): Ok… thanks for coming out. How do you think that went?

Journalist (kind of anxious): well, I think it went ok. It was a little touch and go but you did well overall.

FT (surprised but comforted): Yeah, there is a hiccup or two around certain words, but the closed captioning helps him with that.

Journalist (seeing an opportunity to be positive): yeah, absolutely. It was a pretty smooth experience. Thanks for giving me the time.

FT (increasingly confident): Absolutely, we’re happy to make ourselves available.

I think Fetterman’s team would then see the write-up and it would reinforce to them that the problems they were worried about were not problems at all and that every reasonable person would be able to see through them and understand that, though there were speed bumps in communication, Fetterman was more than capable of handling himself in a stressful, conflict-oriented situation.

In short, because Fetterman wasn’t being exposed to challenging situations or to interviewers who wouldn’t play along with the necessary narrative, they never had to confront their own doubts about his capabilities. They fully believed that their candidate would be met by voters as graciously as he had been met by reporters.

And that is how Fetterman and his team built up enough confidence in his capabilities that he found himself on the debate stage with Mehmet Oz on October 25th.

After all this time of trusting journalists and campaign figures to tell them what could only be appropriately known through direct experience, we got to assess Fetterman’s condition with our own eyes, uncensored and unedited. The picture that had been painted for us these last few months went up in smoke.

Fetterman was a mess. He struggled to pull together sentences that he had clearly been trying to memorize. He answered questions that had not been asked. At one point it seemed as if he was accusing Oz of buying a house from his in-laws for a dollar (which is something that Fetterman did, not Oz). At one point he was completely unable to engage a follow-up question on conflicting statements he had made and simply repeated “I support fracking” three times before giving up on any further elaboration.

A lot of people (including myself) were shocked at exactly how bad things were for Fetterman in that debate. I was well prepared for him to stumble over a question or two, to get some words or a word tense wrong. But he was manifestly ill-prepared to run through that debate. My takeaway was that he doesn’t need to win a senate race, he needs to focus on recovering from his stroke.

The question we had before us was “Is John Fetterman mentally fit enough to be a US Senator?” This is not a question to be answered with a 30-second media clip or the kind of intentionally vicious “what about the gaffs” partisan attacks we expect in the political sphere. This is a question where most observers were showing grace in the face of uncertainty and quietly deferring to medical experts and the people close to him who were best able to make that determination with a generous understanding and, we hoped, a certain ruthless realism. The sensitive nature of this topic meant that it was difficult to ask questions about it prior to the debate. Sadly, instead of using that sensitive nature to make a hard but private assessment of their candidate, journalists and campaign leaders used it cynically, first as a shield to avoid revealing the truth and then as a cudgel to silence dissent.

That is why I think this event may become a totem to represent another disastrous collapse in media trust. They were given an opportunity to do the simplest and cleanest version of their job: go, observe, and tell us what the truth is about a reality we cannot observe for ourselves. What we should have gotten was a steady stream of increasingly worried reports that would have so well prepared us for the disastrous debate, that it would have been a denouement on the tragic campaign. Instead, we were misled for months, causing us to witness a train wreck of shocking proportions. The success of the narrative had left the public entirely unprepared for how much Fetterman had deteriorated.

What strikes me with some despair is that this was such a perfect opportunity for the media to earn back trust. This was a softball pitch to win one for the integrity of the press. Despite our inclination to doubt, learned over two decades of press failures, this was the ideal combination of events that forced us to rely on third-party reports that should be the bread and butter of a non-partisan media. Most of them took it and saw it instead as an opportunity to hide the truth to secure a truly meager political gain.

Praise (and an increased inclination toward trust) should indeed go to Dasha Burns, who put her own professional reputation as a journalist on the line by communicating to her audience her honest opinion of what she experienced. But the response to her attempt to delicately tell the truth was repulsive. It wasn’t just insulting to a journalist trying to tell the truth, it was a warning to any future reporter that deviation from the party narrative will be punished. Even in the midst of a collapse of public trust and crisis that is threatening the entire industry, too many journalists are choosing lies over truth at the drop of a hat, trading the hard-earned currency of public trust for a one percent bump in the polls for their preferred candidate.

Looney Tunes: Super-Rabbit (1943)

We’re jumping over to Looney Tunes this week for a very stupid and silly reason. There has been a push within the Biden administration to label the far-right as “mega MAGA”. I don’t understand why they did this and initially rolled my eyes at it until someone pointed out that it fits perfectly with this cartoon. There is a scene in Super-Rabbit where Bugs grabs his nemesis Cottontail Smith (and his horse) and gets them into some ad hoc bleachers and teaches them a cheerleading chant. Someone realized that you can replace “Bricka Bracka” with “mega MAGA” and now every time I hear that phrase I think

Mega MAGA firecracker sis boom bah

Bugs Bunny, Bugs Bunny, rah rah rah!

This is an adorable short. I actually fear it’s a bit illegible to viewers who are not familiar with the old Superman series, but it also doesn’t seem to care very much if you’re following along. It does a good job setting up Bugs as a superhero reliant on his magical carrots who then sets himself against an absurd one dimensional villain whom we can be comfortable as the target of Bugs’ particular brand of deviltry.

The short ends with a bit of a patriotic deus ex machina (as appropriate for a film made in 1943) when Bugs transforms from a cartoon superhero into a “real hero”, a US Marine heading off to the World War II theater. It’s silly, but cute.

This happens in the opposite direction as well. Reporters will deliberately misunderstand a joke or a polite question in order to give the impression that a candidate is ignorant or out of touch. "Dan Quayle thinks people in Latin America speak Latin!" "President Bush has never seen a supermarket scanner!" I have a rather progressive friend who had totally bought into the narrative that George W. Bush was a moron and that Dick Cheney was the evil power behind the throne making all the decisions. Then, a few years after he left office, she actually met Bush in person when he visited the company she was working for. She was completely shocked to realize after interacting with him that not only is the former President not an idiot, he's actually pretty intelligent.

I’m glad to see us return to Looney Tunes. Truth be told, I’ve never cared for Disney cartoons, even if the alternative was a Ghost & Mrs. Muir episode I’d seen 30 times.

As for the major topic of the piece, good article! Give me a hard-boiled reporter any time over a snooty, elite-university-graduate journalist looking down her nose at us little people as she tells us what to think.