How Rebekah Jones Ruined Faith In Data

In this third piece on the authority crisis, we look at how trust in data can be lost and how it is hard to re-establish once it is gone

Last week, I wrote a positive vision of how to generate trustworthy data. My description is certainly incomplete, but I identified the following patterns with the COVID Tracking Project that established trust within the group and among people consuming the data. These patterns were:

Create an open process for data collection

Perform expert review (without relying on credentialism)

Camaraderie within the organization (friends tend to trust one another)

Transparency in the organization and in how the data is generated and collected

Now comes the more painful part. The baseline component of trustworthy scientific consensus is that we can trust the core data.

If the foundational data is bad, then the whole process will be poisoned and institutional trust is impossible. That is what started happening in Florida in May 2020.

How To Destroy Trust in Data

It wasn’t more than a few months into the COVID crisis that there was a serious challenge to the trustworthiness of the core data project, brought to us by the Florida Department of Health dashboard admin Rebekah Jones. If you are unfamiliar with Jones, I wrote about this story as it was happening and it is (I must humbly say) a fascinating read in light of all we know now.

In May 2020, Rebekah Jones was fired from her position handling the Florida COVID Data Dashboard due to insubordination stemming from her refusal to follow a weirdly simple and inconsequential request from the state epidemiologist. At the time that I wrote about it (which was less than a week after it happened), this all seemed like the media making a mountain out of a molehill.

As the story got out, the details became mangled until Jones settled into this tale of how she was told to “take data off the state’s dashboard… and she believed that smaller Florida counties were not ready to reopen and state health officials didn’t like that.”

This was nonsense. In every interview she gave, Jones was intentionally opaque about how the data she was in charge of was being manipulated, hidden, or used for partisan political ends.

The end result was a massive loss of trust in the data being given by the Florida Department of Health. Driven by Jones and her story, many people began to believe that the Florida DOH was simply outputting bad data and subsequently refused to believe any of it.

I see these objections still. A substantial group of people believes with all their hearts that Florida simply did not report all their COVID cases and deaths and so any reports on Florida should be met with skepticism.

This leads to my first maxim on data and institutional trust:

As soon as there are doubts about the how the data is generated and made public, trust in the results is impossible.

Watching this disaster from inside the COVID Tracking Project was a very strange experience. Jones had worked with us and helped us set up data feeds so we could auto-import data from the Florida DOH. Because we knew her, there was a natural sympathy and a generosity of spirit to what she was telling us about what happened.

But as the story escalated, you could see the people within CTP getting increasingly nervous. As she went national claiming that the Florida data was fake, the experts within CTP kind of stood back cringing at her claims. We all knew that the Florida data was accurate. We never stopped using it for the CTP reporting.

Every month or two after that, some new volunteer would ask why we didn’t use Jones’ independent data site for our Florida data reporting instead of the Florida DOH numbers. Someone would then carefully explain that changing our data input for Florida alone would mean making an executive decision about which health departments we, as an organization, trust or do not trust and that was outside of the mission of the CTP.

But the persistence of this request hinted at the fact that Jones’ story caused many people to lose faith in the validity of the data coming out of Florida’s Health Department and many never really regained that faith. The trust was lost forever.

Thinking back to my vision of how data can be established as trustworthy, we can map how this story destroyed trust in the Florida data at a few key points. I also want to note that I’m not talking about what should have happened, nor trying to point fingers at anyone who distrusted Florida data as being ignorant or partisan. We should recognize that honest people lost faith in the veracity of the Florida data and do a post-mortem on how that happened.

An Insider Expert Casts Doubt

The fact that this story came from an insider made a big difference to the veracity of the story. Jones was working inside the Florida Department of Health and was known to people within the data community as someone we had worked with before. This gave her a presumption of expertise that was enough for some people to cast doubt on the core data.

However, the media handling of this event was atrocious. I wrote about it as soon as it came out and noted that there didn’t seem to be any coherent story about exactly what happened and why it should cause us to cast doubt on the data itself.

Additional interviews with Jones did not bring clarity to the situation. Over the following months, Jones made several national television appearances, received several awards, and yet was unable to articulate how the Florida data was untrustworthy. Indeed, as she pulled hundreds of thousands of dollars from outraged donors for her own “independent” data dashboard, she continued to rely exclusively on the Florida data that she had spent all of her time dismissing.

The genie doesn’t go back in the bottle. The accusation stuck because people wanted to believe it and because it was repeated by NPR, CNN, MSNBC, the Miami Herald, Cosmopolitan, Forbes, Fortune, Washington Post, NBC News, and a slew of other smaller media outlets. Impressions are like concrete; give them enough time to set and they are impossible to alter.

Reporters Had No Knowledge Of The Data Process

At some point we should discuss how the media industry offers enormous incentives for people to humiliate red state governors, even if they do so with lies. But that is a discussion for another time.

Most of the media were taken in by Rebekah Jones’ story and they showered her with praise for it. Yet no one in the COVID Tracking Project ever doubted the Florida data despite the fact that most people in CTP had the same political alignment as most of the media. Why is that?

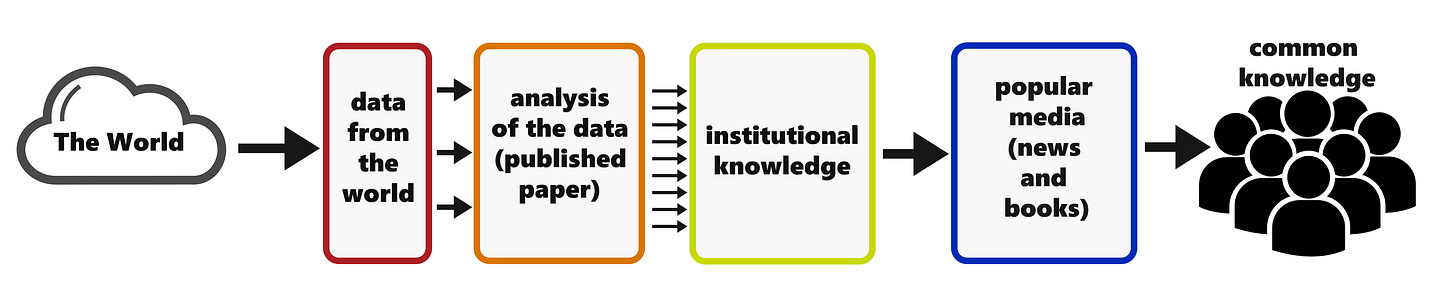

I believe it is because people at the CTP understood the data collection process while the popular media has no idea how any of this process worked. Indeed, as Jones became more and more of a media phenomenon, the data experts within CTP increasingly distanced themselves from her. Her story only made sense to someone who had no context or understanding of COVID data collection and was willing to accept her version of events without any interrogation.

From her interviews, it was clear that the people interviewing her (like Chris Cuomo) were very much out of their depth. Jones could avoid direct questions and dance around the technical details so that her interviewer would simply nod and humbly acquiesce to her version of events because they had no understanding or knowledge foundation from which to interrogate or challenge her.

There Was No Avenue for Rebuttals

The media’s greatest failure in all this was their failure to investigate this question from the position of similarly placed experts within the Florida DOH. A fair-minded investigator would have interviewed someone—anyone—within the Florida DOH and highlighted their objections.

This was not done. Rebekah Jones was treated as inherently trustworthy and the responses from the DOH were treated as boilerplate administrative bullshit. After several rounds of being mocked and dismissed by national media, people within the DOH simply stopped responding to requests. There is no point in communicating with someone who is just going to lie about you.

Jones took to attacking anyone who disagreed with her, even attempting to hack the accounts of people who objected to her lies. Even as no one in the data collection community believed Jones, even as it became increasingly clear to everyone that she was mentally unbalanced and spiraling into absurdity, no one wanted to go public in opposing her.

What would be the point? Imagine if you are a liberal who works with data and knows that what Jones was saying is false… who could you effectively tell? Not a journalist, who would paint you as a right-wing extremist (which is what they did to several Democrat-leaning employees within the DOH who went on record). You couldn’t say anything on Twitter for the same reason: it wouldn’t make any impact. The right would pounce on it, while the left would ignore it, or at worst, attack you, alienating you from your friends and colleagues. That is too much risk for not enough benefit. In the end, most people in the data community just quietly despised Jones while going on with their more important work.

The Aftermath

In the end, Jones was disgraced. The “Forbes Technology Person Of The Year” is a laughingstock and no one thinks about her anymore. Her story has been formally investigated and fully debunked. The people who once promoted her now pretend they have never heard of her.

None of this brings back the trust.

As these events were playing out, I saw them happening and tried to directly address the trust issues it was creating. I wrote about how Jones’ core complaint didn’t seem to make any sense, and how she herself continued to trust Florida data even as she sowed doubts about it. In an excruciatingly long and detailed post, I wrote about how it was functionally impossible for Florida to be manipulating their data.

These may have moved the needle somewhat, but not much. The truth is that even the smallest cracks in data trust can grow into chasms for anyone who is motivated in disbelief. With Jones, the media was eager for a story of corruption and fraud and delivered that story regardless of the truth. After that initial seed is planted, it’s hard to blame people for their skepticism.

Once we are convinced that a source is not trustworthy, it’s a long road out of that belief. I know only one person who moved from Jones believer to Jones skeptic, and it took him months of being keenly aware of the topic and technical enough to ask the right questions before he concluded that Jones was probably lying.

It takes one false expert to destroy the trust and a thousand genuine experts to rebuild it. We see this pattern over and over again.

Disney Shorts: The Musical Farmer (1932)

I’m certainly turning into something of a curmudgeon on the early Disney shorts. I confess a bias toward color over black-and-white, but the monochrome Mickey Mouse shorts have so much energy and personality that it’s hard to dislike them.

In this short, Mickey is planting crops with Pluto until he decides to play a prank on Minnie. Minnie foils Mickey’s antics but comes out of it no worse for wear. The rest of the cartoon is about chickens laying eggs.

It’s hard to describe the visceral joy of these cartoons. This one comes across as a wild farm-themed music video. The energy is non-stop. Sure, the plot is thin, but the excitement and energy are clear. Not a frame is wasted in setting up a gag or making a visual joke. It’s simple and delightful.

Confirmation bias must play a major role here too. The major media was eager to promote Jones' version of events because it confirmed the views that they already held (that FL appearing better than NY must be explainable by data manipulation).

A couple of months ago I heard Charity Dean (the CA public health official who was one of the heroines of Michael Lewis’ “The Premonition” say that Florida didn’t report its deaths accurately and that was a reason for its comparative positive ranking on that measure. If someone as well informed as Dean believes that, it’s really cause for despair.