Every State's COVID Numbers in Context, August Edition

I did this in July as we were seeing an explosion in COVID cases and I felt like it was really hard to gain any perspective on what was going on, especially in comparing the recent case surges in the southern border states to what happened in March and April in the Northeast.

So I’m going to be doing this monthly to try to keep my sense of things across the country grounded. It’s incredibly difficult to keep tabs on all 50 states, especially when the news only focuses on a few enormous states that have lots of cases and lots of deaths… because they have lots of people.

It is my firm belief that every state deserves to know what is going on and they need to know it within the context of other states and other outbreaks so that people can make reliable assessments and grounded judgments.

From what I’ve seen after months of observation is that COVID outbreaks follow regional patterns, so I’ve grouped various (somewhat arbitrary) regions together. There’s a pattern in data journalism where you present one dataset first to establish a baseline. Then you show another data point to give a counter point. You do this to create a sense of drama and narrative as you move along, ultimately building up to the final data point or graph or that really drives home the point you’re trying to make.

I am trying very hard to NOT do that. I don’t have a point I want to make or a narrative to drive home. I have my opinions, but no desire to construct a narrative out of them. Narratives fall apart because new things happen that are unlike the old things.

The biggest change I’ve made is that I’m starting the charts at the beginning of May instead of the beginning of March. The reason is that, as events progress, we are more concerned with the most recent data. Showing 6 months of data means compressing our view of the most recent events. Yes, we get some older context, but I hope we’re moving toward a place where we’ve internalize that older context and can move forward toward the newer stuff.

With that in mind, skip around as you feel led:

Midwest (Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Wisconsin)

Mountain States (Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming)

First Hit (Northeast) States (Connecticut, DC, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania)

Southern Border (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Texas)

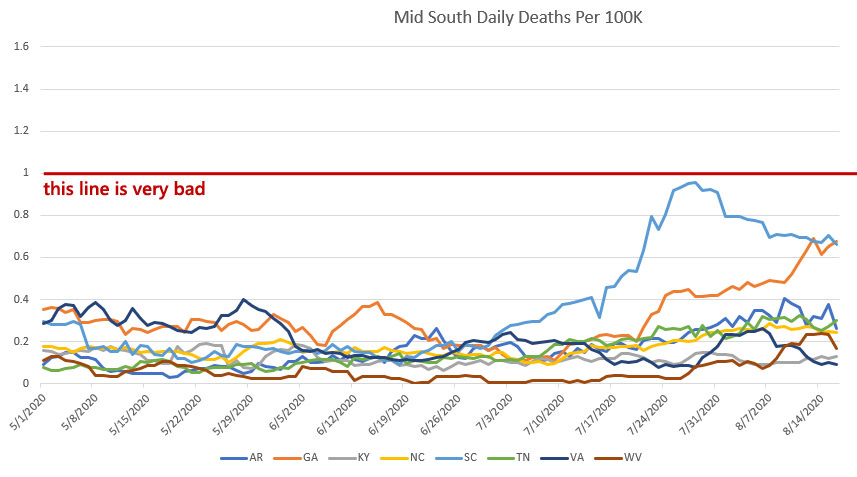

Mid-South (Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia)

Plain States (Kansas, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota)

West Coast (Washington, Oregon, California)

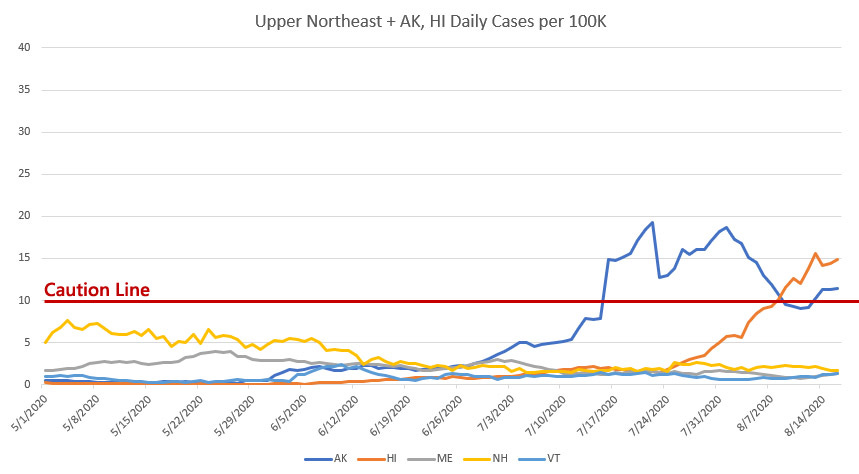

Upper Northeast + Alaska & Hawaii (Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Alaska, Hawaii)

Summary

Disney Shorts - The Robber Kitten

Midwest

The Midwest was the hardest one to make the data cutoff at May 1st, because we don’t really see exactly how bad things got for Michigan in the early stages of this crisis (it was bad), we only see the trailing point of that first wave.

But the last month has been pretty good for the midwest. Only Missouri has seen case spikes and so far those have not materialized as a surge in deaths. They still could (we’ll know when I do this in September) but they haven’t yet.

This is en excellent example of how cases may increase but then stabilize. When we looked at the midwest last month, we were seeing case increases, but they have mostly plateaued slightly above the caution line.

This could go one of two ways. Either we are seeing a stabilization of cases at a point where we don’t get a spike in deaths or we’re in for a case plateau that will linger in the danger zone until a tipping points pushes it into a second wave. I really don’t have the insight to say if it is one or the other right now.

Mountain States

In the last edition, I was very concerned about the mountain states, specifically Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. However, shortly after I wrote that, the cases stabilized and started falling, indicating that these states are recovering from their surges.

I’m honestly a little surprised that Utah saw very little in terms of a death surge while Idaho saw more of a surge in deaths. This is something that I think is curious: If a state can stay below the 20 cases per 100K line, it seems likely they can avoid a surge in deaths. Going over that line (as Idaho rose to over 30 cases per 100K) seems to trigger a serious surge in deaths. We’ve seen this in several regions, not just the mountain states.

It would be nice to see Idaho and Nevada recover more quickly, but they are recovering. We can hope they’ve passed through their first major COVID wave.

Northeast States

Overall, the latest data from the northeast looks pretty good. Cases are fairly low, we’re not seeing a case or death resurgence. This could be an effect of being hit so hard in the early stages of this crisis that vulnerable populations have already been impacted or there is some extent of herd immunity in place. Or it could be the result of good policy. That is not something I’m willing to tackle here.

On thing that is somewhat concerning is the cases-per-death ratios. You may notice that Massachusetts is down substantially from a really awful outbreak that was running well into May. Their cases are well under the caution line and have been since early June. The same is true for Pennsylvania.

Yet, their COVID deaths are both close to 0.2 per 100K. That may seem low because it’s in the context of very high death rates a few months ago. But that death rate is higher than Utah. Scroll back up and note that Utah spent most of the last 2 months with cases well above the caution line (10 cases per 100K) while PA and MA both were well below it. Yet UT has seen fewer deaths in that time than both PA and MA.

That is odd. I don’t know what conclusions I can draw from that other than to note that it is a very odd pattern.

Southern Border

These are the states that have been in the news this last month, especially Arizona, Florida, and Texas. Arizona was a harbinger in both cases and deaths, with other southern border states soon following it.

If I’m permitted an aside, it does bother me somewhat that states like Mississippi fall through the cracks in national reporting. Mississippi and South Carolina were both hit terribly by this recent surge and no one talks about them because they aren’t large states. That bothers me and I can’t explain it past the simple observation that I think these are important places worthy of our attention and concern.

The bad news it that the unprecedented case surges in these states was followed (inevitably) with a surge in deaths. I mentioned in my overview of the states last month that all the data people were seeing signs of a peak but not talking about it because things could always go sideways.

As it turns out, that hope for a peak was justified. Nearly all states in this group have seen reduced cases and are in the mitigation stage now as they work to reduce cases and manage the medical complications inherent in a surge.

We expect things to get better, though we are not sure how quickly they will get better. There is still much uncertainty around how much immunity a case surge of this size confers to the population. It’s something we’ll learn fairly soon.

The Mid-South

This is a truly strange set of states when it comes to COVID data. We can see Georgia and South Carolina COVID surges rise in tandem with Tennessee and Arkansas. Yet South Carolina saw a heavy death toll, Georgia has seen less, and Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina are following the same death patterns despite seeing incredibly different curves in case surges.

This is incredibly weird and I have no theory that explains or contains this phenomena. It is possible that we are still waiting for deaths to show up in the data for Tennessee but in the meantime, they have had a full month in which they have had six times as many case as Massachusetts but have the same death rate.

That’s really weird and I’m skeptical of people who have a ready answer for why this is instead of scratching their heads and admitting that this is, at the moment, a largely unexplained phenomena.

Plain States

The plains states are my go-to example for my theory that it is possible to have cases above the caution line and yet manage to keep the infections under control.

With a few exceptions (Nebraska in May, Oklahoma in July) these states have managed to keep their infections under the “20 cases per 100K” threshold and there is honestly very little differentiation in COVID deaths between them.

Maybe that will change this next month. If it does, I suspect it will come from Oklahoma. But there is reason to hope that the plain states will be largely spared from this crisis.

West Coast

California looks good from its inclusion as a “Southern Border” state and then pays for that when I include it in the west coast states.

For whatever reason, be it lock-downs, demographics, city density, or population distribution, northern California, Oregon, and Washington have done fairly well. Cases remain low, but they are also concentrated in urban centers.

This is good news, I’m not sure what else I can add to it.

Upper Northeast + Alaska & Hawaii

My deepest apologies to everyone who was offended last month when I called people from these states “weirdos”. You’re not weird, you’re just unique.

If I were to make any update, it would be to note exactly how fast things can go sideways with this virus. Last month, only 4 weeks ago, the generally accepted view was that Hawaii had conquered COVID. Cases and deaths were both rock bottom. Since then, Hawaii has seen a fairly startling rise in cases, up above the caution line.

This does not mean the virus is out of control, it is simply an observation that it is incredibly difficult to fully eradicate. There seems to always be the risk of re-introduction and infection.

Summary

My sense of things from the last month to this is largely a sense of relief. Last month we did not know how bad the southern states were going to get. Now, we have a better sense of what a late-stage surge is going to look like and, while I’m not encouraged by the existence of late-stage surges, I am encouraged that we’re not looking at anything close to the impact that we saw from the initial stages of this virus in March and April.

We’ve gotten better at managing this virus. We have better medical mitigation, better testing, we, as a population, are more careful than we were six months ago. The states managing these surges are not shutting down hospitals or issuing stay-at-home orders. The closures are more targeted and the hospitals have learned how to carry on elective procedures while also managing a COVID surge.

This is all good news. The bad news is that we’re going to spend the next few weeks absorbing the impact of these recent surges and that impact is rough. There will be tens of thousands more deaths in the next month. That is a difficult reality to recognize and accept.

We all want this to come to a conclusion, but the conclusion is still in the distance. But we are getting there.

Disney Shorts: The Robber Kitten

He’s a kitten! And he’s a robber! An adorable kitten robber!

Ambrose the kitten decides that he is too big for a bath and runs away to become a bandit kitten (after stealing all his mother’s cookies). He runs into an actual bandit and spins a yarn of his supposed conquests in an effort to appear bigger than he is. When the bandit shows his true colors, Ambrose quickly retreats to his mother, eager for the security of home and the comfort of knowing his “proper” place.

There is a pretty standard narrative, a basic morality tale about the consequence of stepping out of bounds of one’s assigned place in life. The character of “Robber Bill” is delightfully animated and cast, but the overall structure is something you would expect out of one week run from Calvin and Hobbes.

"If I’m permitted an aside, it does bother me somewhat that states like Mississippi fall through the cracks in national reporting. Mississippi and South Carolina were both hit terribly by this recent surge and no one talks about them because they aren’t large states. That bothers me and I can’t explain it past the simple observation that I think these are important places worthy of our attention and concern."

I think another reason to be concerned is that it's indicative of the media and our national conversation still not having moved beyond the point of fixating on the largest raw numbers, a point we should be past.

Great analysis and terrific graphs. Thank you for both, as well as for your intellectual honesty in this whole endeavor. Two questions: (1) Have you explained somewhere how you picked the levels of the caution line and the very-bad-death line? They seem like reasonable judgment calls but I'd like to understand your thought process better on both. (2) Have you played with graphing deaths/case to see if anything interesting pops out of the comparisons? You have mentioned that ratio a few times.