Covid Exposure: Seattle as Ground Zero

The beginning of the Covid pandemic in Seattle was defined by bumbling bureaucracy, heroic academic dissidents, a rapid private sector response, and a useless media apparatus

In all the rhetoric of the last years, it often feels like there isn’t a very good history of what March-May of 2020 actually felt like at the time. There were a lot of takes that didn’t age well, both on the “this isn’t a big deal” side and the “pandemic wildfire” side and we tend to see a lot of those dunks because dunking on people is fun. But as I’m reviewing the day-by-day events of 5 years ago, it’s important to really capture what people were thinking at the time and why. Most people were being rational with the information they had. The problem was that this information was either incomplete, patchy, or lacking so much context that it wasn’t valuable.

The more I review the details and knowing what we know now, the more I’m convinced that the people who hold the most responsibility are the within our public health institutions. The story of the early pandemic is one of catastrophic failures in the functionality of our public health apparatus followed by shallow narratives and groupthink disguised as expertise. These are the people and groups who should have guided the public and public policy with a steady hand. Instead the most valuable and important data and actions came from individuals, volunteers, academics, and the private sector.

Start at the Beginning: January - February 2020

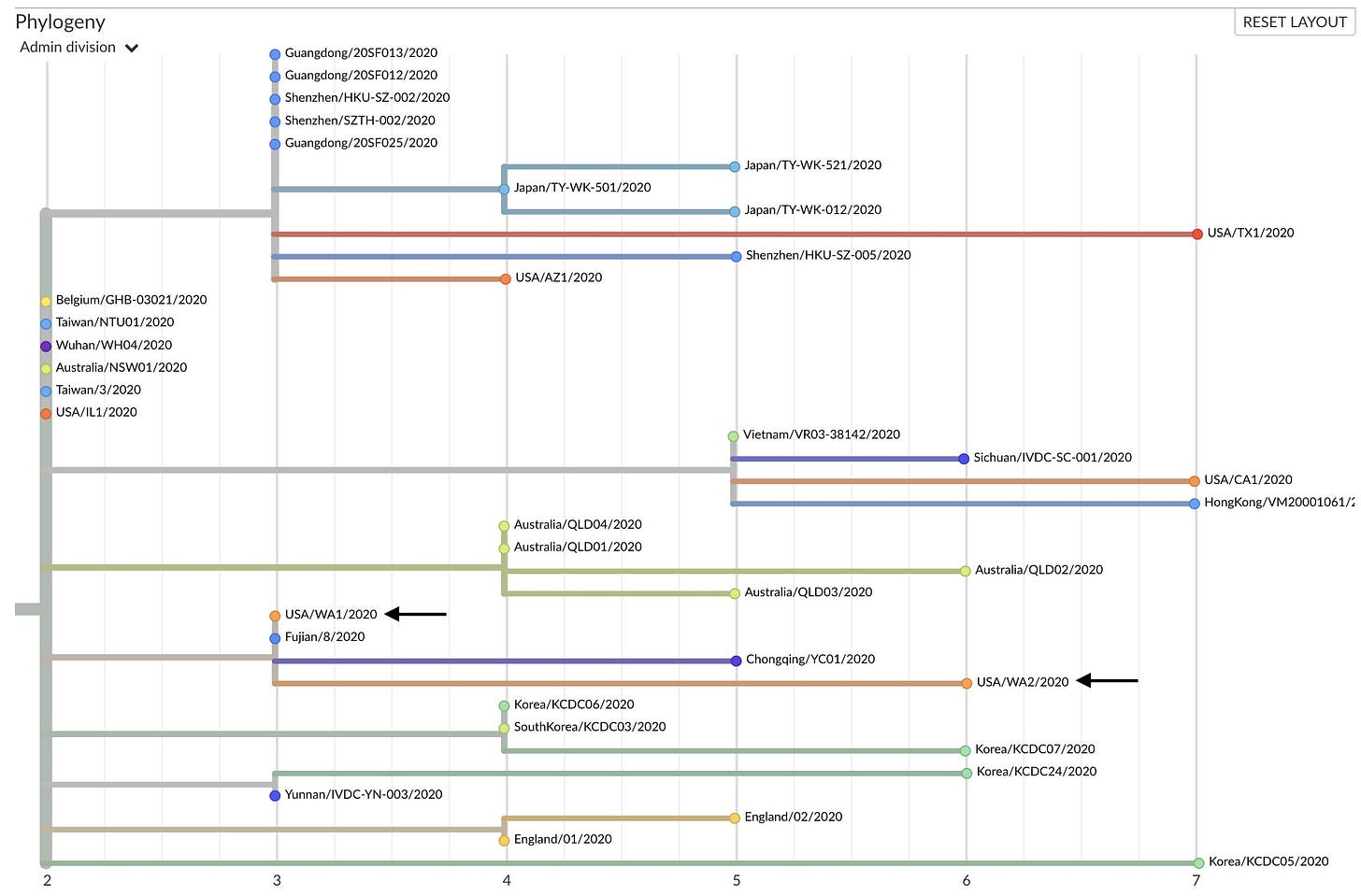

The first case of Covid detected in the United States was sampled on January 19th from a man in Snohomish county just outside of Seattle. He had recently travelled back to Seattle from China and was quarantined for several days. In the following weeks, no further cases were detected.

As I was kept tabs on this story and watched for additional outbreaks, I initially concluded that the quarantine worked. There was no explosion of cases, we had successfully found our first Covid case and kept it from spreading. That was comforting. Maybe our institutions really can get a handle on this.

What no one knew at the time was that Covid was quietly spreading through Seattle from that very first viral introduction. In fact, there were so many cases in early and mid February that they were being detected in a flu surveillance study at the University of Washington. They weren’t being detected as Covid because the CDC had sent out faulty test kits, but there were enough of these “not the flu” cases that it was causing the flu surveillance team to become suspicious.

The testing situation was one of the earliest institutional failures of the pandemic. Lacking a functional CDC test kit, UofW researcher Dr Helen Chu requested permission to test her lab’s swabs for Covid with a test that her team had developed. She was denied by both federal and state officials. Sensing the urgency of the moment, Dr Chu went rogue and by Feb 25th she and her team were testing the swabs using their own unapproved Covid test. The immediately identified dozens of cases, including 2 fatalities.

It’s important to note that even in the early parts of the pandemic, our institutions were way behind. If you were listening to the CDC or Washington Department of Health, you wouldn’t know what was going on. But if you were following virologists on Twitter, you would learn the quarantine of that original patient had not worked and that Covid had been spreading since that introduction in mid January and we were looking at hundreds, possibly thousands of cases in Seattle.

Even when this news became more widely known in early March, the sense of urgency and rapid responses came from the private sector. Within a week, Microsoft effectively shut down their Seattle offices while Governor Jay Inslee was begging the federal government for permission to test people. People were keeping their kids home from school before the state issued any school closing statements.

At the time, I lived less than a mile from Microsoft’s main campus and very close to the Life Care Center of Kirkland where the first Covid death was recorded. Traffic near my house evaporated overnight. Everything got quieter. It was like watching and entire city hold its breath.

I wanted to help in any way I could. When I heard that there was a team of volunteers trying to collect and publish Covid data, I jumped at the chance to join them. I worked with the Covid Tracking Project collecting and cleaning Covid data. This was somewhat embarrassing because collecting and reporting core pandemic metrics was obviously the CDC’s job, but the CDC was caught entirely unprepared.

March 2020 - The First Lockdowns

The next stage of the pandemic was when everything was happening all at once.

From the media side, the first big concern was that it was racist to blame China for Covid. In March 5th, a NYT reporter noted that “the teachers I’ve spoken with are much more concerned about racism, xenophobia and rumors associated with the virus than the virus itself.” Reporters repeatedly grilled Trump on why he was calling it “the Chinese virus” as if this mattered at all given the reality on the ground.

This all seemed like a world away from the response in my city. We had just discovered that Covid was running wild in our city, school was cancelled, businesses were closing, and the Governor was mulling a “shelter in place” order for all residents. We were preparing for an immediate future of full hospitals, rampant sickness, and over-worked healthcare professionals.

It is into this environment that our local institutions and bureaucracies went into failure mode. I contacted my local Medical Reserve Corps to see how I could join or help. This is an organization sponsored by the HHS whose sole purpose is to supplement existing response capabilities in times of emergency. They were not accepting volunteers. In this time of emergency, there would be no meetings, no trainings, no volunteer events. The institutional backstop that we had built for just this situation was made of gossamer.

For a short time, I volunteered at a food bank until the state ordered it to close. They said they would replace the volunteers with National Guard to help provide food for the homeless, but that was simply a lie. The food was left to rot.

In the absence of opportunities to help in my city, I helped with the data. The data situation at CTP was fascinating in its simplicity. We set up twice-daily shifts to manually check the Covid data state by state. We tracked tests, positives, hospitalizations, ICU population, and deaths. We also tracked demographics when they were available. For over a week, the Washington state Covid dashboard went down while they were trying to upgrade it and I was checking every county health department website every day so we could still keep track of the Washington numbers. This ragtag group of volunteers became the bulwark for public health data for the United States.

We became very familiar with the many artifacts of this kind of data. For the first few weeks, testing kits were hard to come by so many places were only testing the sick. This meant that the case-to-fatality ratio was extremely skewed with some people claiming it was as high as 7%. There was a lot of focus on the positivity rate (out of 100 tests, how many were positive?), but this was a hard metric to follow because some states didn’t report their negatives or the number of tests that were being administered. If you don’t report your negatives, then your positivity rate is 100% but everyone knew that a 100% positivity rate wasn’t possible.

As March wore on, it was becoming clear that Seattle was not seeing the exponential explosion that we had been warned about. We had a high number of Covid cases but we also knew for certain that Covid had been circulating in the Seattle area for weeks. We increased our testing but the more testing we did, the further our positivity rate dropped.

The anticipated surge in hospital utilization never arrived. I was hearing from doctor friends that the hospitals were actually empty because all non-emergency procedures were cancelled and people were scared to go to the hospital.

It was into this world of data that I made what I consider to be my first big error: I believed that we had stopped Covid. I thought that the early detection from our brave research scientists in defiance of a bumbling public heath apparatus had given us the early warning we needed. I believed that maybe the early and rapid response from our tech sector tipped the scales in the right direction and we never hit the tinderbox point of rapid city-wide infection. If we had managed to wrangle this potential pandemic, then that meant that there was a place for caution, lockdowns, and school closures. We could keep this thing under control and save lives.

Then we saw the data start to roll in from New York.

(This series will continue later this week. If you are not a paid subscriber, please consider supporting this newsletter.)