Babies and the Bible

A guest post from Bible visualization expert Robert Rouse on Biblical baby names and what that tells us about religion in America.

Editor’s Note: When I started “getting big” online, it was due to data visualizations. I gave a lightning talk on data visualization for the Ignite speaking event and started using a variety of tools to dig through data, trying to make it comprehensible and telling a story in the process.

That is how I ran into Robert Rouse (first online and eventually in real life). Robert has a unique passion and talent for data visualization and has done some truly spectacular work combining data visualization with Biblical data. He is the host and author of viz.bible, which is a gold mine of Biblical visualizations.

Today’s newsletter is a guest post from RR about Biblical names in our modern American culture. Enjoy!

Last year, 23 people named their son Judas and 20 named their daughter Jezebel. The rest of you made a better decision. All of my kids are named after heroes of the Bible and I wonder how many parents do the same thing. What influences their choices? Has the dilution of our Judeo-Christian heritage led to a decline in biblical names?

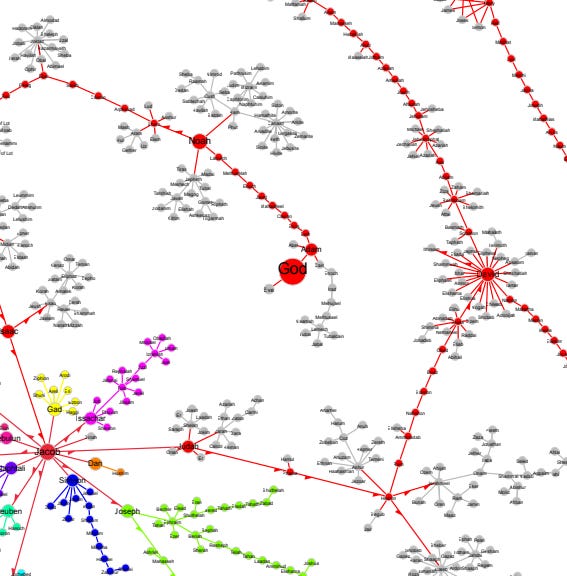

A decade ago, I created a network diagram tracing the genealogies from Adam to Jesus and the tribes of Israel.

It resonated with a wide audience because humans yearn to know about our ancestral heritage and connections to important people of the past. Modern infographics about baby names go viral for similar reasons. So, I decided to merge my Bible names file with the Social Security Administration baby names data all the way back to 1880. Here’s what I found.

Lifetime Trends

Our view of history is biased by experiences from our own lives and family stories. Looking at a 140-year trend gives us a more objective picture of how cultural influences shape religious identity in children’s names. The chart below shows the percentage of Americans born each year whose name matches the English spelling of one of the names in the King James translation of the Bible (KJV).

I was born 40 years ago in 1981, a peak time for Bible name popularity. This chart gives new meaning to the phrase: “over the hill.” Our nation is on the downward slope of that hill with no sign of slowing. The data confirms a move away from assigning Christian monikers to children which correlates to cultural changes I’ve observed in my lifetime.

The other big downtrend was during a wave of mass immigration at the end of the 19th century. Foreign names and misspellings at Ellis Island are a better explanation than religious influence in those years. There was an uptrend in the decades covering the Great Depression, WWII, and Baby Boom. Gen X babies with Boomer parents were part of another positive slope from 1970-1980. Your guess is as good as mine to explain those turns, but I recommend this generational analysis by Zach Bowders for more insight.

Popularity and Gender

Dear John, congratulations! You’re number two on the list of most popular American names for the last century. Take comfort that your namesake is Jesus’ most beloved disciple. The chart-topper is James, also a disciple and the other “son of thunder” (see Mark 3:17). Robert (hey, that’s me!) is number three. That one comes from a combination of German words for “bright” and “famous” but is nowhere in the Bible. Here’s the top 10 list with biblical names highlighted.

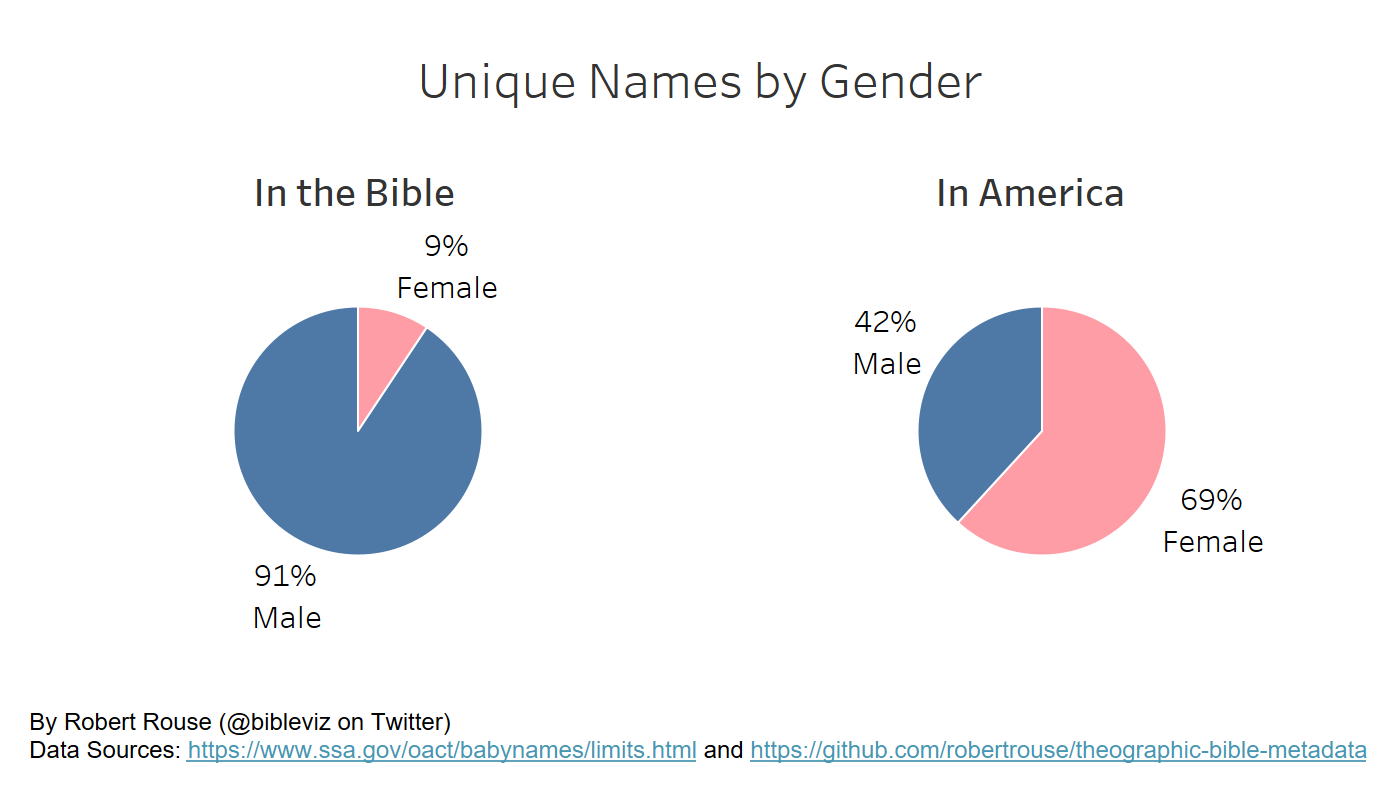

Why are almost all of them male names? These gender-split charts give us some clues.

There isn’t a deep well of religiously anchored options for girl names, so people get more creative when naming their daughters. In the United states, there are far more distinct names for females vs. males. That dilutes the distribution leaving fewer of them at the top. If you want your daughter to have a Judeo-Christian identity, Mary would be the most popular choice followed distantly by Elizabeth, Sarah, Anna, Ruth, Deborah, Rachel, Martha, Julia and Judith.

91% of biblical characters are men, but that doesn’t make it a misogynous book. John Dyer, an expert on intersections between faith, society, and technology, published an article in Christianity Today describing his data-driven approach to this issue using the Bechdel Test. This looks at three criteria to measure the representation of women in books and movies: (1) there are at least two named women who (2) talk to each other (3) about something other than a man. Dyer found that scripture meets and exceeds that benchmark in pivotal narratives. Still, there aren’t many biblical women’s names to call your sweet baby girl.

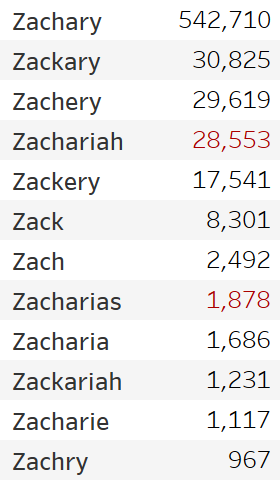

Zack, Zachary, and Zachariah

No analysis is ever complete without handling some ambiguities. Consider Zachariah, a name assigned to 27 distinct individuals across the old and new testaments. The most common English derivative, Zachary, doesn’t count in any of the above charts. Here’s a small list of how many people use related spellings but aren’t included as a biblical name. Those in red match the KJV spelling.

Imagine the same issue with Matthew/Matt, Thomas/Tom, Mary/Marie, or Elizabeth/Beth and you’ll get some idea of how hard it would be to count all the alternatives influenced by the Bible. Plus, our spelling conventions have changed since the King James translation was published in 1611. If some clever, hard-working analyst were to link all the derivative names to the originals, we may find some difference in the trends showing declining identification with religious figures. If you are curious enough to do that, get the Social Security Administration files here and the data on Bible names here then tell the world what you found.

Data volume and quality from the dawn of the 20th century may also affect the trendline. Does anyone believe that the numbers from 1880 or even 1980 are as accurate as the data from last year? Hey, at least we aren’t counting anything important like COVID deaths.

Looney Tunes: Bunker Hill Bunny

There is something funny about watching rootin’ tootin’ Yosemitie Sam play “Sam Von Schamm the Hessian”. Sam’s style is so rooted in an American cowboy archetype that his playing the original combatant of the American project is comically incongruous.

There is also something inherently funny about a Revolutionary War being fought between two individuals, each in solitary occupation of their own fort. The gags are excellent and flow well together and this short makes good use of that strategy in which the final joke is an elaborate, wordless, drawn-out piece of physical comedy.

It’s a bit heartwarming to see at the end that Sam abandons his mercenary position to join Bugs in the fight for independence.